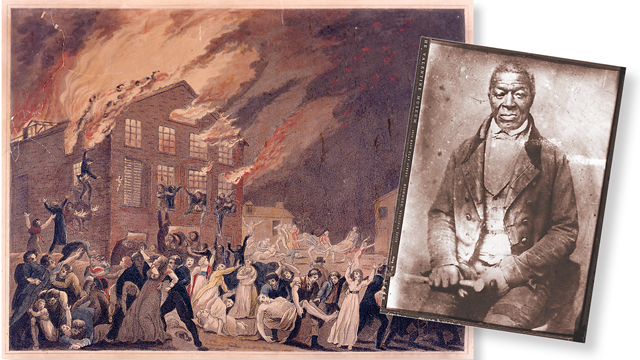

On the day after Christmas in 1811, an enslaved African American blacksmith named Gilbert Hunt was visiting his wife downtown at a home where she was a servant. While there, news reached them that the nearby Richmond Theater had caught fire. The mistress of the house then revealed that her 17-year-old daughter, Louisa Mayo, had gone to the theater. Louisa had taught the blacksmith how to read. With this in mind, Hunt raced to the scene to try to help. He found utter chaos.

“The scene surpassed anything I ever saw,” the blacksmith later said. “The wild shrieks of hopeless agony… the uplifted hands, the earnest prayer for mercy, for pardon, for salvation.” For that evening’s performance, more than 600 people had packed into the poorly designed theater, which had a capacity of only 500. The inferno so consumed the building that escape proved impossible for many.

With the help of a white man, Dr. James D. McCaw, Hunt found a ladder to reach the upper windows, from which desperate souls were flinging themselves. McCaw broke a window, then handed down survivors for the black man to catch. In this way, the two men saved as many as twelve women from certain death, working nearly to the moment of the building’s collapse. The official death count of the Richmond Theater Fire amounted to seventy-two, mostly well-to-do white victims, including the Governor of Virginia and Louisa Mayo.

For his efforts, the enslaved blacksmith was lauded as a hero of the deadliest urban disaster in American history at the time. Twelve years later, Hunt performed a similarly heroic feat as a volunteer firefighter when the State Penitentiary caught fire. With the main entrance engulfed in flames, he hoisted the brigade’s captain onto his shoulders to cut a strategic opening in a wall. With this act, the hopeless situation was completely reversed. None of the 244 prisoners died in the fire. “The next day, I spent making hand-cuffs for the poor fellows,” Hunt later wrote in his memoir. “I didn’t think, the night before, I should have this to do.”

At some point, the American hero saved enough money to purchase his freedom. He briefly immigrated to Liberia in 1829, but returned to Richmond within eight months. In 1840, he was appointed deacon of First African Baptist Church. Richmonders long remembered his service to the city – including forging military tools during the War of 1812. Forty years after these deeds, newspaper stories and pamphlets circulated to raise money for his care in old age.

Photos: Cook Collection, The Valentine