In 1970, in order to satisfy a federal mandate to desegregate Richmond Public Schools, Judge Robert Merhige, Jr. ordered the implementation of a busing program that would attempt to achieve racial balance in the school system. At the time of the order, enrollment in the Richmond Public School System was approximately 70 percent black and 30 percent white. Since neighborhoods were still largely segregated, neighborhood schools remained so as well. The goal of busing would be to reflect this seventy-thirty balance within each school.

Opposition to the busing plan was powerful and widespread. Protests rocked the city. In 1970, on the first day of school, 5,000 white students did not show up for class. Notable exceptions were the children of Virginia Governor A. Linwood Holton, who sent one daughter, Tayloe, to John F. Kennedy High School (now Armstrong High School), and a son and a second daughter, Anne Holton, to Mosby Middle School. That year, 13,000 students were bused. The next year, after the U.S. Supreme Court upheld busing, the plan expanded to 21,000 students.

In response, white families continued to flee the city. When it became clear that the imbalance could not be remedied with Richmond’s dwindling population of white students, Judge Merhige ordered the Chesterfield County and Henrico County school systems to be consolidated with the city schools, in order to flip the racial composition to 70 percent white and 30 percent black. But the 4th District U.S. Court of Appeals reversed the cross-county decision, a reversal that was later upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court. With the suburbs exempt, Richmond lost 12,000 white students in four years. By 1986, the year busing ended, white students made up less than 15 percent of enrollment in Richmond City Public Schools.

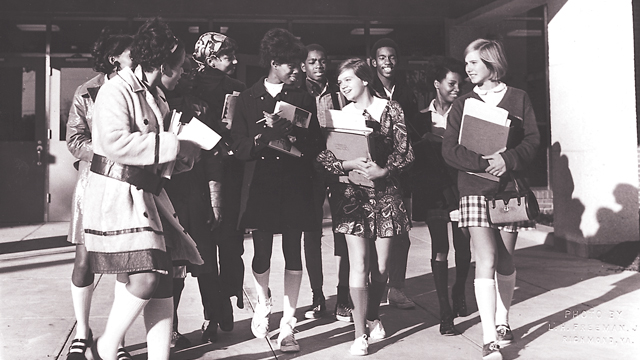

Photo: The Valentine, L.H. Freeman, Jr.