In the Victorian era, before the widespread establishment of city parks, the concept of the rural cemetery arose as a solution to urban congestion. Designed with the living in mind, rural cemeteries were planned to mimic the countryside near urban centers. They were meant for picnics, strolling, and inspirational views. In Richmond, in the 1840s, two prominent citizens named Joshua Fry and William Haxall sought to build a rural cemetery. Other burial sites here were either cramped churchyards or rigid, gridded landscapes, like the city-owned Shockoe Cemetery.

Inspired by the Mount Auburn Cemetery outside of Boston, Fry and Haxall bought forty-two acres on the high banks of the James River. Just outside of city limits at the time, the area was rural, with creeks, rolling hills, and river views. The founders intended to keep it that way as Richmond grew around their cemetery. But opposition to their plan was strong and loudly amplified by the Richmond Whig (a newspaper published between 1824 and 1888). Some Richmonders were suspicious of a privately owned cemetery and feared a profiteering scheme. Neighbors worried about plunging property values. Less well-off citizens suspected the cemetery would only be accessible to the wealthy. Many claimed that a cemetery so close to the waterworks would contaminate the city’s water supply. But Fry and Haxall persisted in their plan, which became easier once they gave up ten acres as a waterworks buffer. By 1848, four years before Richmond’s first public park was established, the cemetery had been designed and mapped by John Notman, who had also designed Capitol Square.

Dedicated in 1849, Norman named it Hollywood Cemetery for the many mature holly trees already onsite. Indeed, to live up to the greenspace mission, he kept a lot of the trees, many of which survive today. The cemetery also featured fountains, a creek, and two lakes separated by a waterfall. Wildlife, including swans, made the area their home.

In the following decades, Hollywood grew and was populated by wealthy families, in addition to ordinary citizens – all of whom were white. Internments exploded during the Civil War with the burial of about 18,000 Confederate soldiers. For the growing collection of elaborate monuments, the cemetery became a sculpture garden as well. The special symbolism of the dead was rendered in mausoleums, tree stumps, lambs, angels, and upside down torches. More unique and personalized stonework and ironwork proliferated as well, such as pet dogs and a train (to memorialize a death by train crash). In 1874, a florist shop and greenhouse opened. For its natural beauty, botanical delights, and artistic intrigue, Hollywood became so revered that prominent families, like the Mayos, began to move their dead for reinterment there. Jefferson Davis, the president of the Confederacy, was reinterred in Hollywood Cemetery in 1893.

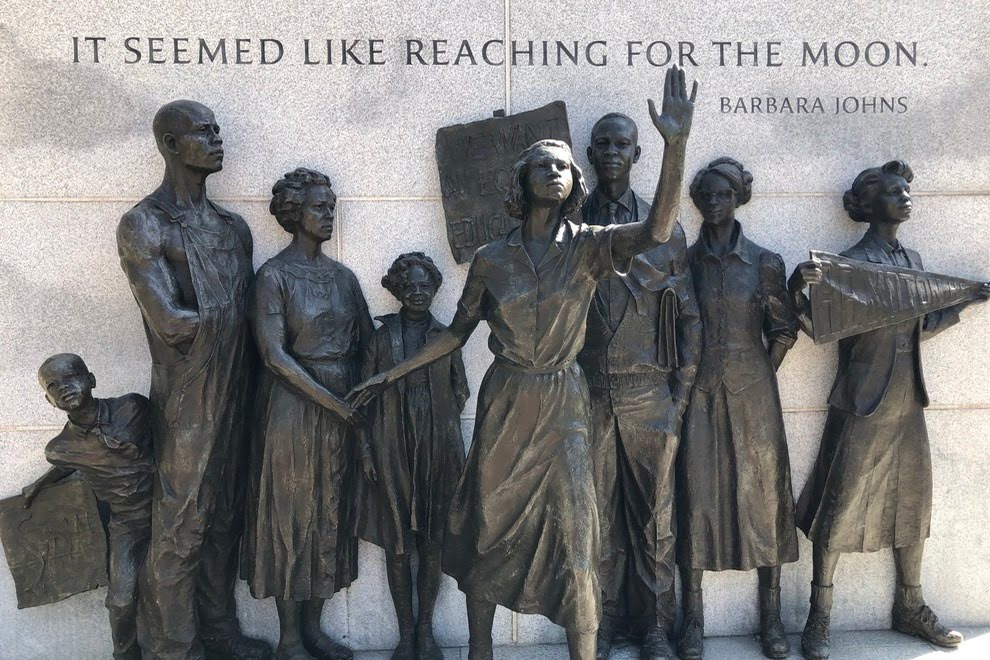

Hollywood lived up to its promise as a place of both private remembrance and public gathering, at least for white citizens (all Richmond cemeteries were officially segregated until 1970). Starting in 1866, more than one hundred years before Congress declared Memorial Day a national holiday, crowds of Richmonders filled Hollywood on May 31 each year to remember their war dead, the vast majority of whom were from the Civil War. Into the twentieth century, Hollywood grew to 135 acres and became a tourist destination for its beauty and illustrious grave sites, from artists to barons to political leaders. Six Virginia governors, two Supreme Court justices, and two U.S. Presidents are buried in Richmond’s rural cemetery. Presidents Circle contains the gothic tomb of our fifth president, James Monroe, in addition to the grave of our tenth president John Tyler. That grave is marked by an obelisk, shown here.

Photo: Cook Collection, The Valentine