The Virginia Constitution of 1869 established a statewide system of free public schools. The schools evolved in the 1900s with both Jim Crow restrictions and Progressive Era reforms. Even progressive movements, though, were rife with racism, and Black activists rarely had a seat at the table.

Reforms were directed to segregated white schools first. Beginning in the 1930s, Black plaintiffs challenged segregation at the graduate and professional school levels. In 1950, the NAACP decided that it would no longer file lawsuits seeking equal educational facilities for Black and white students – only those that sought to end school segregation. The 1954 Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas decision was a judgment in five different consolidated lawsuits that challenged the constitutionality of segregated schools.

One of these came from Virginia in Davis v. Prince Edward County, Virginia. On April 23, 1951, sixteen-year-old Barbara Johns led a student strike against inadequate facilities at the grossly overcrowded Robert Russa Moton High School in Farmville. The NAACP took the case when students agreed to seek an integrated school rather than improved conditions at their Black school. Howard University-trained attorneys Oliver Hill and Spotswood Robinson later filed a suit.

One of these came from Virginia in Davis v. Prince Edward County, Virginia. On April 23, 1951, sixteen-year-old Barbara Johns led a student strike against inadequate facilities at the grossly overcrowded Robert Russa Moton High School in Farmville. The NAACP took the case when students agreed to seek an integrated school rather than improved conditions at their Black school. Howard University-trained attorneys Oliver Hill and Spotswood Robinson later filed a suit.

A state court rejected their suit, finding that Virginia was seeking to equalize its schools. Equality often connoted only the presence of a physical school. Equity, however, required all students to receive the same quality of education. Hill and Robinson appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, where they combined with four other cases, including Brown v. Board of Education.

On May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court unanimously declared that “in the field of public education, the doctrine of ‘Separate but equal’ has no place.” In stating that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal,” it explicitly overturned Plessy v. Ferguson. Brown II, issued in 1955, and decreed that dismantling segregated schools could proceed with “all deliberate speed.” This led to various racist strategies to resist the integration of Virginia public schools.

The state-sanctioned policy to block the desegregation of schools, known as Massive Resistance, began when Virginia Senator Harry F. Byrd directed the General Assembly to close any school that was ordered to integrate by the U.S. Supreme Court. On January 19, 1959, both the Virginia State Supreme Court and the U.S. Supreme Court declared that these new laws were unconstitutional.

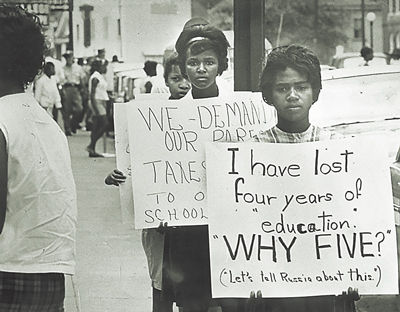

Regardless, Prince Edward County supervisors opposed integration by ending all local support for schools, which caused them to close from 1959 to 1964. White officials created private schools to educate the county’s white children with support from state tuition grants and county tax credits. There were no such provisions for Black children. Instead, some attended school in nearby counties or at makeshift schools in church basements. Others traveled out of state. Some students never finished their education, even after schools reopened.

In the early 1960s, residential segregation and local “freedom of choice” plans limited integration of public schools. This ended in 1968, however, when the Supreme Court’s decision in Green v. County School Board of New Kent County, required schools to show actual progress in desegregation. In many areas this meant busing students to achieve a racial balance of Black and white students. Busing resulted in the exodus of white families from cities to suburbs.

Today, the impact of white flight, redlining, and generations of Virginians living in de facto segregated neighborhoods means that the racial makeup of many schools are still starkly majority white or majority Black.

Photos: courtesy Virginia Museum of History & Culture