Troy Michel remembers how energized she felt when, as a child, she checked out books on her own from the old Tuckahoe Library on Parham Road. “It was so cool to have my own library card that I could put in my fake purse,” she says, laughing.

Today, the mother of seven sees the same glee in her children’s faces when she takes them to visit the Glen Allen Branch Library in Henrico County, just minutes from their home. “Even the three-year-old has his own card,” she says. “And they all have to carry their own books.”

Michel, whose kids range in age from six months to sixteen, says library excursions check many boxes for their family. There’s something for everyone (no matter the reading level) and special activities like story time or crafting engage her kids in different ways. Staff are friendly and ready to help, and the library is there when weather makes it hard to be outside. Perhaps best of all, she adds, the library is free.

“There can be bandanas to color, little toys to play with, a sock puppet show… always things for [the children] to do,” she says. “We usually have to make a day of it, and I find it hard to get them to go home.

“It’s great to get out of the house, and for us, it’s cost-effective,” she adds. “I love that the county provides this for us.”

The Michel family isn’t alone in their library love. In 2020, the pandemic forced libraries to close for a time and change how they provided services and access. Now, local systems in the Richmond region report strong demand for everything libraries have to offer, from gathering and work spaces to community activities. Circulation (number of items checked out over a given period of time) and number of visits have either returned to pre-pandemic levels or are steadily moving in that direction, say library leaders in the City of Richmond, Chesterfield, Henrico, and the Pamunkey Regional System, which encompasses the counties of Goochland, Hanover, King and Queen, and King William.

As Michel says, visiting the library is good for everyone. “You don’t know what you don’t know.”

Richmond Public Library

The pandemic was full of “starts and stops,” notes Richmond Public Library Director Scott Firestine. Initial closings in the spring of 2020 led to the rise of curbside services. As the virus ebbed and flowed, libraries would occasionally shut their doors and wait for the increase in COVID-19 cases to flatten. “2021 was tough. We began to emerge in 2022, but in 2023, it feels like we’re surging back to normal,” Firestine says. “Circulation is returning to the level it was pre-pandemic, and door counts are increasing, too.”

Firestine isn’t surprised to see the recovery, pointing to people’s needs for information, community, and education.

“Our Founding Fathers really understood that access to education and information was a cornerstone of our democracy,” he says. “[Libraries] are a constantly evolving community space with no barriers based on economics… a community where anyone can walk in. It is free to access the information that you need.”

And that information is readily available, thanks to technology. Firestine is talking about the library’s tenth branch – what he calls its website – open every day of the year, every hour of the day. “You can get an electronic library card, check out audiobooks and music, and check out movies and view them on a device,” he says. “We had [online services] OverDrive and Hoopla before, but [usage] has increased four-fold since the pandemic. In June 2020, we were circulating 6,000 items a month online; now, it’s 24,000 a month.

“Our big takeaway from our master planning process is [to have] less emphasis on the physical book. Today, it’s about access instead of ownership,” he says. “The library of the past was about overwhelming people with books. It was comforting, and you were assured you could find anything. Today, we can still get you that answer, but we don’t need millions of volumes on the shelf.”

In some cases, access has a price, though, in the form of paywalls that limit what people can find for free on their own. Firestine credits Mayor Levar Stoney and Richmond City Council for critical support. “The city has been very generous,” Firestine says. “The mayor and city council have restored and increased funding so we can increase access [for patrons].”

For many families, it’s the in-person experience that matters most. To encourage visits, RPL locations are reimagining interior design to create open and welcoming environments. Story time sessions draw parents with young children, offering support for early childhood literacy. Easily accessed office equipment – computers, printers, scanners, and copiers – help remote workers. Author visits and guest lectures can bring the abstract into focus.

As RPL celebrates its centennial year, Firestine says, it’s more important than ever to recognize what has remained constant alongside what must change.

“I think people are reading more; they’re just consuming information in different ways,” he says. “I really believe that information is evolving, and the way we consume information is evolving. People want what they want, and they want it quickly. As we continue to grow, we’re going to continue to adapt to those needs.”

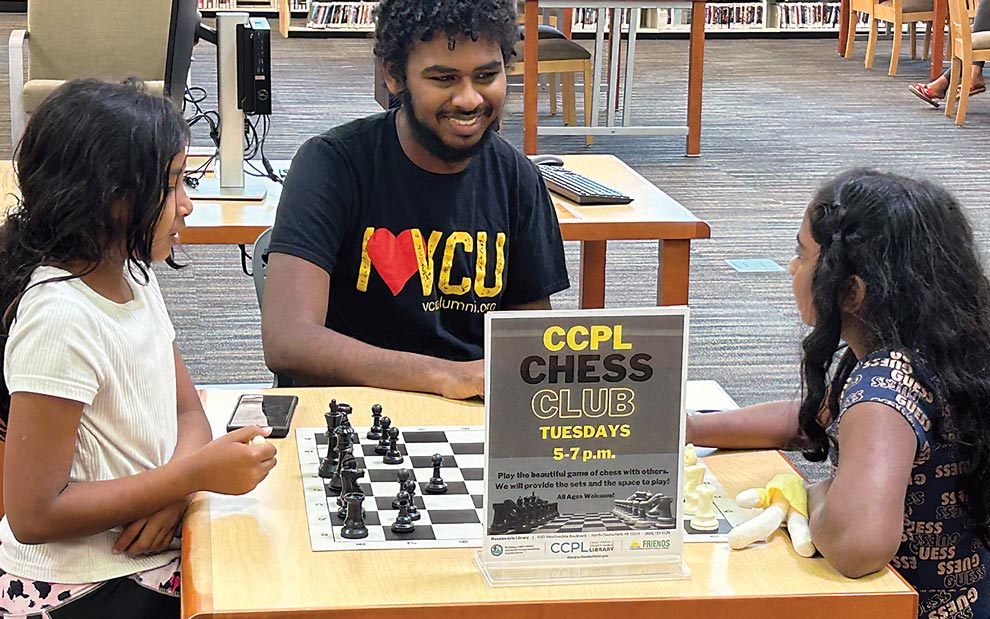

Chesterfield County Public Library

With a new Midlothian library expected to open late this year or early in 2024, a new Enon branch, expansions to the Ettrick-Matoaca and La Prade branches, and a new library situated in the northwest corner of the county, Chesterfield County’s library system is growing to meet residents’ needs.

“We have 350,000 cardholders and slightly less than 1 million items in the collection,” says Michael Mabe, director of library services for Chesterfield County. “We want more materials and more meeting spaces in a variety of sizes, more outdoor reading spaces, and living room areas in each library, where librarians can have open conversations [with patrons] to find out what they’re looking for.”

In fact, Mabe says most visitors are likely to interact with reference librarians as they roam the floor, electronic devices in hand, rather than at a central information station. “We make sure everybody [on our team] understands our approach is to help the customer access the collection from their perspective,” Mabe says. “We are more inclined to ask, ‘What are you looking to learn today?’ instead of ‘What book are you looking for?’”

Of course, people still want books. And CCPL was quick to find a way to put books in people’s hands. “We reopened four days after the shutdown, with curbside pickup, to a booming business,” Mabe says. “Customers who were big library users to begin with just assumed libraries would make themselves available. Those customers who may not have been aware of the depth and breadth of our services are now big-time users.”

In-person interactions are close to pre-pandemic levels, Mabe says, and there’s been an increase in people taking advantage of online services. “Virtual services have always been there, but the number of folks who are checking out [virtually] has increased,” he notes. Plus, more virtual programming is available. “We have access to more authors and performers who are willing to [appear] from the comfort of their location.”

Mabe, who holds a doctorate in public administration, knows first-hand the impact a library can have. As a child, he would visit the public library in his hometown of Parma, Idaho. “That library represented not just a space or place for books … there was culture, information, literacy, learning, [and] art,” Mabe says. “I went, and I’ve never turned back.”

That community service is available to all, he notes. “If we were to open and nobody came, we’d still be doing the community a service because it’s available,” he says. “People need to make a choice to use [their library], to select what they want, then they can realize it’s a lifetime thing. After formal education is over, you can still be learning. Our core responsibility is access, but we believe that if we do it from a learning perspective, it enhances the overall customer experience.”

Pamunkey Regional Library

“We’re happy to say that we are back to full services and full programming,” says Jaime Stoops, deputy director of the Pamunkey Regional Library. “Our circulation numbers are really starting to rebound, and we’re offering story times and early literacy programs for kids. It’s great to be back and offering those programs.”

With ten locations in Hanover, Goochland, King and Queen, and King William counties, and the towns of Ashland and West Point, the regional system covers a lot of territory. But because any Virginia resident eighteen years of age or older can obtain a borrower’s card for the system, people aren’t necessarily bound by geography.

“The pandemic really did highlight that we have a lot of database and digital materials, plus streaming services through Kanopy,” Stoops says about the on-demand streaming video platform used by public and academic libraries. “There were a lot of things already available through the library website. [The pandemic] highlighted it and made people pay more attention.”

Still, the system moved quickly to offer curbside pickup and outdoor programming and provided mobile hotspots for Internet access, Stoops says.

“Our staff was invested in wanting to still offer services,” she says. “There are so many stories of people saying the library helped them survive the pandemic by providing something to read. I’m so proud of our staff and everybody who went through this pandemic with us.”

Some pandemic adaptations have proven durable. Curbside pickup is still available upon request. A few book clubs that were held virtually are now hybrid, allowing those who want to meet in person the chance to do so while others participate remotely. Mobile printing, made available because of capacity restrictions inside branches, enables customers to send documents electronically from their laptops or phones to a kiosk for easy retrieval. Families can enroll in the summer reading program via an app that also tracks progress.

During the pandemic, staff throughout the Pamunkey library system added content to their YouTube channel. How-to videos were popular, and many publishers were permitting story time videos, previously prohibited because of copyright law. Initially lacking the materials and training needed, staff partnered with VCU’s communications department to obtain the technology and learn the how-tos.

“It was really impressive,” Stoops says. “It was neat to see how quickly and creatively we could get some content out there for people who couldn’t come in. You learn things about people – like who knows how to make sourdough bread.”

According to Stoops, kids seemed to appreciate seeing familiar faces on their screens when Miss Carolyn or Miss Tracy presented their story times. “Now we have a treasure trove of virtual story times and literacy activities on our channel,” says Stoops says.

The system has returned to offering outreach programs in schools and community events, and groups are returning to take advantage of on-site programming. Customers are asking for extended hours, more craft programs, and more study spaces. And new spaces are on the horizon, with both the West Point and Montpelier branches slated to move into new spaces.

“We’re still understanding how our customers’ habits and patterns changed, and that will affect how we move forward,” Stoops says. “[But] It’s an exciting time to have people back in the buildings again, utilizing all the spaces.”

Henrico County Public Library

Usage of Henrico County’s library system – which includes five designated libraries and four branch locations – is almost where it was before 2020.

“If you look at statistics, we’re not quite back, but very close,” says Director Barbara Weedman. “Our circulation is very close, and visits are not quite what they were before the pandemic, but use is heavy and increasing at a fast clip. We’re pleased [the libraries] are feeling busy, robust, and active.”

Weedman credits HCPL’s recovery to increased flexibility and versatility, noting that during the pandemic staff moved quickly to offer curbside pickup and highlight online options that included e-books and virtual programming, where demand surged. The library system also acquired one hundred mobile hot spots, thanks to a grant from the company Meta, which provided portable Internet access for those who needed it.

“All of our online learning saw an increase,” she says. “[Eventually,] I think we’ll see the dust settle. But what it shows us is what we think of all the time – we are providing options to customers, to families. We want to offer different formats, because that’s how humans operate.”

Weedman, who has been with the system for fifteen years and director for five, says there has been a dedicated effort to broaden offerings within the library system. In the past decade, three large libraries were built – Fairfield, Libbie Mill, and Varina – all of which have digital media labs with resources to help community members create and learn while experimenting with new technologies, like 3D printers. The Sandston branch was refreshed in 2022 with new paint, carpeting, energy-efficient light fixtures, A-frame shelving, upgraded audio-visual equipment, a resurfaced parking lot, and eco-friendly landscaping. The North Park branch will soon have a refresh of its children’s area.

“We’ve had a great investment from the county and the community, and it shows,” Weedman says. “We really did aim to get lots of community feedback [for the new libraries] and to honor the communities the new libraries are in, both stylistically and with services. We are getting a lot of positive comments about our collection and our materials.”

Services run the gamut from a demonstration kitchen at Varina to a recording studio at the Fairfield location. All newer libraries have special areas for teens, with dedicated staff for programming. The Henrico County library system is also adding story times for children on the autism spectrum and programs for adults with disabilities.

“Those new libraries gave us the opportunity to get feedback from the community and build things that enhance the community’s life,” Weedman says. “We want to add programs for people who may not have as many options and also be very aware of neurodiversity. We are at a stage where we can think about how we serve everyone.”

Weedman uses a garden analogy to describe what’s been happening in Henrico County.

“For years, we’ve been planting seeds and thinking about the future and trends so we can move with the changes,” she says. “I can now look back and see some of the things we’ve developed from inception and how they’ve been received. We see things blooming.”

If Henrico mom Troy Michel’s experience is any indication, the garden is in great shape. “[The kids] like the adventure of seeing how the libraries are structured differently,” Michel says. “Each library has different books. One of my sons is obsessed with Sonic the Hedgehog. We can go to different locations and find different [Sonic] titles.

“As a mom, [I know] the kids can get familiar with one place, but if I take them to another library, it piques their interest,” Michel adds. “It’s beautiful that libraries offer such wonderful things.”