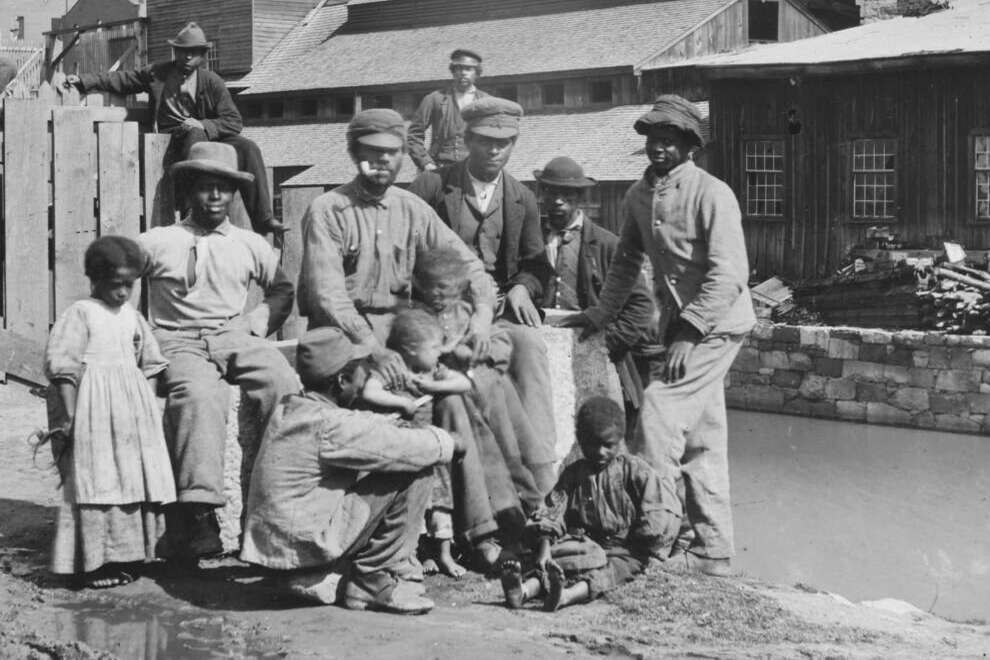

By the end of the Civil War, the James River and its tributaries were too polluted with industrial waste for swimming. Desperate for relief during the summer, Richmonders headed for park fountains to cool off. The fountain in Monroe Park had become a popular, yet unofficial, wading pool by the turn of the twentieth century. Then in 1919, city officials responded by converting Shields Lake in Byrd Park into a public swimming facility – for whites only.

Immediately popular, Shields Lake (pictured above) drew more than 100,000 white visitors per year. Despite this clear popular demand, black residents in segregated Richmond would not get a swimming pool for another twenty years, when Brookfield pool opened in 1939. Public swimming pools came under suspicion during the polio outbreaks in the mid-twentieth century, though the pool remained open.

When the legal defeat of segregation happened in 1954, the prospect of integrating Shields Lake loomed over city officials. Instead of integrating the lake in 1955, the local government – citing public health concerns and expensive repairs – opted to suspend swimming at Shields Lake.

A few years later, amid accusations that it was unfair for African Americans to have a pool while whites did not have anywhere to swim, the city closed the Brookfield pool in Northside as well, noting a need for repairs to that facility that were never specified.

With no public swimming pools or lakes in Richmond for the next ten years, the city avoided the issue altogether. It was not until 1967 that municipal pools returned, with the opening of the Fairmount, Battery Park, and Blackwell facilities. They proved to be so popular that the city introduced above-ground portable pools in 1969. In 1970, a fourth permanent city pool called Randolph Pool opened at Lombardy and Idlewood. Today, nine public pools – both indoor and outdoor – are in operation around the city