Fifteen years before Rosa Parks sparked the modern Civil Rights movement, a young Black lawyer opened a law practice in Richmond. Born in this city in 1907, Oliver Hill had grown up in Jim Crow Virginia, attended Howard University Law School, and returned to Richmond in 1939 with the explicit intention of dismantling segregation.

Hill began by visiting the State Library and Supreme Court on Capitol Square. At that time, the building also housed the offices of many segregationist lawyers from Senator Harry Byrd’s political organization, which had maintained a stranglehold on Virginia politics and racial progress. Undaunted, the lawyer found a sympathetic clerk at the library, who allowed him to check out books over the weekend, as long as they were returned first thing Monday morning. The research paid off. Within a year, this young lawyer won his first civil rights case in Norfolk.

Over the course of an astonishing sixty-year career, Hill litigated cases that both paved the way for the modern Civil Rights movement and built on its success. He won equal salaries for Black public school teachers, secured the right for Black citizens to serve on juries, advanced voting rights, helped to dismantle segregation on transportation, sought employment protection, fought housing discrimination, and won free bus transportation for Black public school students.

Over the course of an astonishing sixty-year career, Hill litigated cases that both paved the way for the modern Civil Rights movement and built on its success. He won equal salaries for Black public school teachers, secured the right for Black citizens to serve on juries, advanced voting rights, helped to dismantle segregation on transportation, sought employment protection, fought housing discrimination, and won free bus transportation for Black public school students.

Knowing that real change required the change of the law as well, Hill ran for Richmond City Council in 1948 and won a seat. He was the first Black politician elected in the city since Reconstruction. Though he very narrowly lost reelection, he paved the way for future Black leaders, like Mayor Henry Marsh who was elected thirty years later. Hill’s most famous accomplishment, however, reached beyond city and state lines and delivered the death blow to segregation on the national level.

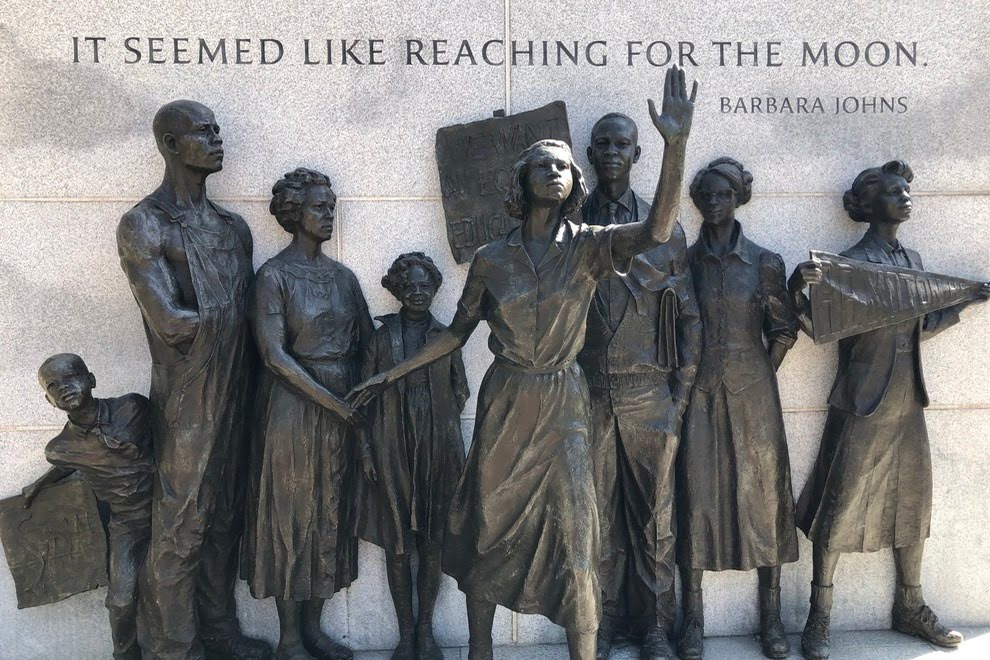

In 1951, this attorney agreed to represent the Black students of Prince Edward County, who had walked out of their classroom in protest of substandard conditions. That case was eventually combined with four others in 1954 and went to the U.S. Supreme Court as Brown v. Board of Education. He stayed on as a member of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund team that argued the case. They won in a unanimous 9-0 decision which declared segregation in public education illegal. Even more importantly, the decision established legal precedent for desegregation in other institutions.

With the contributions of his law partners Samuel Tucker and Spottswood Robinson, his Jackson Ward law office became one of the busiest civil rights firms in the south. The practice filed more civil rights suits in Virginia than any other firm in the south. Through all this, Hill’s litigation won $50 million for Black teachers and schools. And though their court victories did not always immediately translate to real-world results or progress, they never let up. They took on Massive Resistance, as Virginians rejected the Brown decision. In 1960, six years after winning Brown, the victorious lawyer spoke at the Richmond School Board meeting that finally sanctioned the first step of school desegregation here. A few months later, two Black female students walked into Chandler Junior High School.

When Hill retired at the age of ninety-one, this Richmond lawyer had advised three U.S. presidents, co-founded the Virginia State Conference of the NAACP and served as its director for twenty years, and won the American Bar Association Medal, their highest honor. In 1999, he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, our nation’s highest civilian honor. Lofty as this award was, perhaps the most fitting honor came in 2005, when the old State Library and Supreme Court building, where he’d had to sneak around to do his early research because of his race, was renamed for him. Two years later, in 2007, Hill died at the age of one hundred, and his body lay in state at the executive mansion in Richmond.

Photography: courtesy The Valentine