In 1886, the Shriners – also known as the Ancient Arabic Order of the Nobles of the Mystic Shrine – established a Richmond chapter called Acca Temple. A secret society not unlike the Masons, the Shriners embraced Orientalism, an aesthetic and scholarly fad at the time, as an identity. Now regarded as an echo of colonialism, Orientalism perpetuates stereotypes of Asian cultures, particularly Islamic culture. At the time, Shriners wore fez hats and invented what they referred to as ancient legends loosely based on Islam.

In Richmond, Acca Temple took the concept to a decadent level when they built their headquarters across from Monroe Park. The building, which opened in 1927, cost $1.75 million to construct. Its 176,000 square feet included an auditorium with seating for 5,000, a ballroom, a pool, a restaurant, forty-two hotel rooms, a bowling alley, office space, and a gym. But more astounding than its size was its arabesque design and décor. Two 100-foot minarets flanked the building. Gold and silver leaf adorned ceilings and walls, along with $100,000 worth of imported ornamental tile. Fake jewels studded the auditorium curtain, in order to mimic a “rich sultan’s tent in ancient Arabia.” Despite this appropriated glamour, the Shriners crafted a humble slogan for their creation: Richmond’s Own Theater Run By The People, For the People.

Indeed, Acca Temple built the auditorium to serve as a cheap public movie theatre. By selling tickets, the Shriners intended to pay for their extravagant complex, share its beauty, and contribute to the arts. On opening night on October 28, 1927, citizens watched a silent film, accompanied by a 25-piece orchestra. Matinee tickets went for thirty-five cents; evening performances cost fifty cents. Obviously, this was not a sound financial strategy, especially as the Depression hit. In 1935, the Shriners defaulted on their mortgage.

In 1940, the City of Richmond bought the building to make it a true public venue. The auditorium hosted plays, concerts, and touring Vaudeville and Broadway shows. The downstairs ballroom became a Big Band hot spot. Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong played there. To cover the $100,000 yearly operating costs and to attract big names, the city had to sell a lot of tickets, so performances welcomed all races. But segregated seating didn’t work during the rollicking dances. The building commissioner attended one and remarked, “The dance was hardly underway fifteen minutes before it was almost impossible to tell which was the white side.” According to state law, this theatre “for the people, by the people,” could not serve all people at once. Officials tried to ban whites from a Count Basie Orchestra show, which caused an uproar. So they decided to abandon dancing altogether. In 1941, the Fats Waller Orchestra played the last ballroom show. There was a reserved section for white spectators, who were not allowed to dance.

In 1940, the City of Richmond bought the building to make it a true public venue. The auditorium hosted plays, concerts, and touring Vaudeville and Broadway shows. The downstairs ballroom became a Big Band hot spot. Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong played there. To cover the $100,000 yearly operating costs and to attract big names, the city had to sell a lot of tickets, so performances welcomed all races. But segregated seating didn’t work during the rollicking dances. The building commissioner attended one and remarked, “The dance was hardly underway fifteen minutes before it was almost impossible to tell which was the white side.” According to state law, this theatre “for the people, by the people,” could not serve all people at once. Officials tried to ban whites from a Count Basie Orchestra show, which caused an uproar. So they decided to abandon dancing altogether. In 1941, the Fats Waller Orchestra played the last ballroom show. There was a reserved section for white spectators, who were not allowed to dance.

Richmond used the complex in various ways. All kinds of performances continued in the auditorium: Elvis Presley, Aretha Franklin, and Bruce Springsteen, among many others. But the hotel rooms were converted into office space. The bowling alley became a police firing range, and the pool was used for police training, too. In 1956, the Richmond Symphony Orchestra moved in. The doomed ballroom became a recreation area for soldiers.

Today, the Shriners have renamed and reinvented themselves as a philanthropic organization that operates children’s hospitals throughout the country. Through the years, their old Richmond headquarters has cycled through renovations and renaming. In 1994, a $4.2 million renovation led to its reopening as The Landmark Theater. Most recently, in 2014, it reopened as Altria Theater after a $63 million renovation.

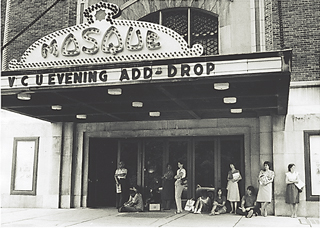

Through these changes, however, the spirit of the venue remains. From hosting psychedelic rock shows to Henry Kissinger speeches to James Brown concerts to VCU events, this theatre has weathered a troubled past to fulfill its initial democratic promise: It’s a theatre for all people.

Photography: courtesy The Valentine