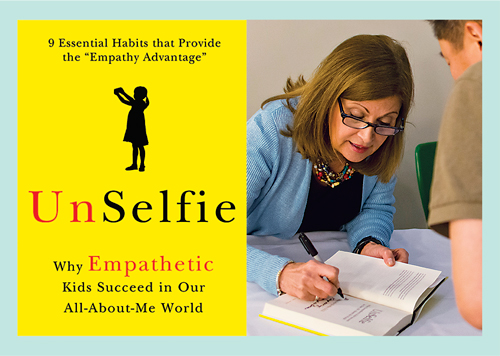

When author and parenting expert Michele Borba spoke in Richmond earlier this spring, her message was clear: Parents need to focus on building empathy, resilience, and confidence in children. Borba, a former teacher and mom of three who has her doctorate and has written thirty books on children’s issues, shared several examples of compassion in action including the story of the Bald Eagles. In 1994, a group of fifth-grade boys in Oceanside, California, decided to shave their heads to preserve their friend’s dignity during cancer’s brutal chemotherapy treatments. Soon after, they were dubbed the Bald Eagles.

Now, raise your hand if watching your child show this level of caring for others would make you feel as though you had done something right as a parent.

When children have a sense of empathy, they own the ability to reach out and respond in more caring and compassionate ways to others. Studies have shown, however, that in the last thirty years, empathy is on the decline. In fact, the incoming college class has had a 48 percent drop in empathy along with a 58 percent increase in narcissism.

A globally recognized parenting, bullying, and character expert, Borba has appeared on The Today Show more than a hundred times, as well as Dateline, Anderson Cooper 360°, NBC Nightly News, and many others. Ten years ago, she became so alarmed by the drop in empathy that it prompted her to begin a study on empathy with a goal to strengthen children’s empathy and resilience, and help break the cycle of youth violence.

“A lot of the Mayberry/June Cleaver era is gone, and the impact of our individualistic, reality show culture causes me real concern,” says Borba, who examined everything from the Killing Fields of Cambodia to the Columbine shooting. “Sitting on a bench on the Killing Fields was one of the lowest times in my life. To my left was a 5-story glassed building filled with skulls, and in front of me was a tree covered with ribbons – each signifying a child who had been beaten to death at the spot.”

But it was when Borba spoke to parents in Littleton, Colorado, just before the Columbine school shooting (right after telling her husband that’s where they should be raising their sons) that she came to a significant realization. “Watching the massacre unfold on television was when I recognized there was a seismic shift happening in our children’s culture. If it could happen in Littleton, it could happen anywhere.” The Columbine shooting prompted Borba to begin studying youth violence specifically, during which she recognized empathy as an overlooked core antidote to reduce bullying, racism, and aggression.

Another pivotal point came when Borba spoke at the US Air Force Academy in 2008, and one young cadet asked some probing questions: “With a moral ozone crisis and the breakdown of character, how can I be an ethical warrior with integrity when I lead troops in combat?” The follow-up was transformational for Borba, and set her research on a whole new path: “So in all your research, what habits did you find that highly empathetic and ethical people use to stay true to their beliefs and help others?” He continued, “What did Mother Teresa and Nelson Mandela do?”

So how did Borba respond? “I didn’t know the answer, but I realized I had been focusing too much on the dark side, and I had never thought of empathy as comprised of learned habits. From that point on my question became, ‘How do you help children turn good?’”

After reading fifty biographies of great moral leaders such as Ghandi and Mandela, she discovered “ethical warriors” were not born, but made, largely by parenting styles combined with the habits they developed. “Empathy is the foundation for kindness and compassion, and everything we want for our kids and our world,” says Borba, “but we cannot just instill empathy, we must insist on it.”

Borba recently visited Collegiate School in Richmond to talk about the product of her 10-year study, her book, Unselfie: Why Empathetic Kids Succeed in Our All About Me World. “What I learned is that kids are hard-wired for empathy, but if left unfinished, the potential lies dormant. It is not so much the temperament of a child, or stirring up a fluffy, soft emotion, as much as it is the deliberate, intentional teaching and modeling of empathy.”

For Borba, writing Unselfie revealed nine crucial habits that we can teach our kids so they will do the right thing – even when parents are absent – and develop caring mindsets. “What we want is for kids to see themselves as good people and their actions to match those beliefs.”

Developing Empathy

Research shows that from day one, infants are given to empathy, but this responsiveness must be nurtured. “The best way to foster empathy is for children to witness and experience it,” she says, adding that unlike genetics or most temperaments, empathy can be cultivated. Parents should ask themselves regularly: What has my child done or seen that would stretch – or shrink – his or her empathy growth?

A good start in developing empathy in kids is to teach emotional literacy. This can be done by teaching that all feelings are okay, but some ways of dealing with them are not helpful. “Children need our help learning to cope with feelings in productive ways,” says Borba, who offers a few strategies for parents.

“We are dealing with digital natives in a world where the Internet is here to stay and emotional literacy is a dying art,” she says, quickly adding that no one learns emotional literacy by facing a screen. “Consequently, kids must be taught to stop, look another person in the eye, and ask, ‘How are you feeling?’”

Learning self-control is also a big part of empathy, and a quality that will foster sensitivity and self-awareness that will serve kids well their whole lives. There are several tools to which parents have access that will help.

“The first step is to start looking for those countless little everyday moments we can use to help kids learn to put on the brakes,” says Borba, who emphasizes that simple instructions that parents give dozens of times a day should not be underestimated. Reminders like “No cookies right now, dinner is almost ready” or “No loans before allowance day” have more impact than parents might think.

But the real prize comes when parents teach kids to push their own inner pause button. “Your child may barrel straight into every task right now, but your ultimate goal is gradually to stretch his ability to control those impulses and learn to wait at his level,” says Borba. One simple way parents can start is by timing how long your child can pause before those impulses get the best of him. Take that time as his “waiting ability” (even if it’s only two seconds) and then slowly increase it over the next weeks and months.

“When a child utilizes self-instruction during the moments of temptation, it is a significant determiner of whether he is able to say no to impulsive urges and/or wait.” Parents should practice together until that new habit kicks in and he can self-instruct when he feels those impulses taking over.

Practicing Empathy

Even if practice doesn’t make perfect, it is likely to bring improvement. The goal is to try to achieve mutual understanding – listening to and paraphrasing each other’s feelings until both people feel understood. Parents can help kids name their difficult feelings such as frustration, sadness, and anger, and encourage them to talk about why they’re feeling that way. “Practice with your child how to resolve conflicts by considering a conflict you or your child witnessed or experienced that turned out badly, and role-play different ways of responding.”

In addition to practice, parents can set limits for kids to establish clear boundaries, along with a reminder that the limits are based on a concern for their welfare. “Some resistance is inevitable, but raising a caring, respectful, ethical child is and always has been hard work,” says Borba, adding that no work is more important or ultimately more rewarding.

Simple strategies such as no-phone zones and requiring eye contact during conversation are a good start. And one easily overlooked element that might surprise parents is that children actually need unstructured play time not just to cultivate empathy, but for their overall mental health. “A good old-fashioned childhood of cloud-gazing, leaf-kicking, and hill-rolling is being replaced by screens, earplugs, flashcards, and tutors,” she says, adding that it is no coincidence that at the same time, reports show that stress is mounting to new heights in kids, while their mental health has plummeted to a 25-year unprecedented low. “Unstructured play time, where you use those core relational skills such as taking turns – that is where you learn and practice empathy.”

Practicing empathy requires daily repetition. “Whether it’s helping a friend with homework, pitching in around the house, or routinely reflecting on what we appreciate about others, increasing challenges make caring and gratitude second nature and develop children’s caregiving capacities,” says Borba.

What’s more, parents need not hesitate in requiring gratitude every day. “We need to stretch our children so they feel for others,” says Borba. “Children need practice caring for others and being grateful. It’s important for them to express appreciation for the many people who contribute to their lives.”

Studies show that people who engage in the habit of expressing gratitude are more likely to be helpful, generous, compassionate, and forgiving. These are all traits that are at the very core of empathy.

Empathy is just good for kids on every level. “They’ll have better relationships throughout their entire lives, and strong relationships are a key ingredient of happiness,” says Borba. “In today’s workplace, success often depends on collaborating effectively with others, and children who can empathize and are socially aware are also better collaborators.” This is perfectly illustrated by Pink Shirt Day, the movement that started in Vancouver, Canada, when one boy told his friend he was being bullied because he had worn a pink shirt. The friend took action, recruiting anyone he could to wear a pink shirt to show support. “He thought maybe a dozen kids would show up in pink on the designated day,” says Borba, “but it caught on, and well over a thousand kids arrived in pink. Now Pink Shirt Day is an anti-bullying movement that has spread as far as New Zealand.”

Living Empathy

When practicing empathy begins to develop into naturally living empathy, parents have reached the ultimate goal.

“Caring is very low on our radar, according to a Harvard study; the message is not getting to our kids, and our culture isn’t helping in our narcissistic world,” says Borba, who urges parents to teach to both sides of the report card. “It’s crucial that children hear from their parents and caretakers that caring about others is a top priority, and that it is just as important as their own happiness,” she says, adding that even though most parents and caretakers say it is a top priority for their children to be caring, often children aren’t hearing that message. Parents should declare it on a regular basis: Empathy is always we, not me.

Since empathy is largely caught, not taught, parents and caregivers must be mindful of what they are modeling. “What I discovered is that it is the little, unplanned things; a spontaneous moment,” says Borba. Parents should ask themselves: When is the last time I emphasized how much caring matters? Did I voice my pride in him for helping his siblings or that he remembered to smile and be kind?

Consider the daily messages you send to children about the importance of caring. For example, instead of saying to children, “The most important thing is that you’re happy,” you might say, “The most important thing is that you’re kind and that you’re happy.” Borba says every kid also needs real responsibilities where they routinely help with household chores and siblings, and only praise for uncommon acts of kindness. “When these routine actions are simply expected and not rewarded, they’re more likely to become ingrained in everyday actions.”

The key word here is initiative. And once kids begin to take initiative at home, it tends to spill out into other areas of their lives. “Make it the norm for kids to take action by urging them to look outside themselves. Broaden their worlds by first modeling empathy, and then help them find ways they can stick their necks out for others,” says Borba. “Instill the moral courage to speak out and do what is right by equipping them with ways to make a difference, whether it is joining a cause to reduce homelessness or improving the plight of abused animals.”

Living empathy is contagious. In her book, Borba tells the story of Christian Bucks, a Pennsylvania second-grader, who noticed that some of his classmates felt lonely during recess. Bucks proposed to a teacher to install a playground Buddy Bench, an idea he had seen on a brochure. A Buddy Bench is a designated seating area where students feeling lonely or blue can send a subtle signal that they need a friend. This one second-grader took action, and the school got on board. Buddy Benches are now popping up across the United States.

Almost all children can empathize with and care about a small circle of families and friends. When empathy starts at home, the challenge is to help children learn to care about someone outside that circle, whether it is a new child in class, the school custodian, or someone who lives in a distant country.

“New behavior habits are what we are really trying to establish in our children,” says Borba. “Empathy is like a muscle. The more you use it, the stronger it gets.”

Nine Essential Habits that Provide the Empathy Advantage

1. Emotional Literacy

2. Moral Identity

3. Perspective Taking

4. Moral Imagination

5. Self-Regulation

6. Practice Kindness

7. Collaboration

8. Moral Courage

9. Altruistic Leadership

From Unselfie: Why Empathetic Kids Succeed in Our All About Me World