Elementary school teacher and mom of two Kisha Christian gets excited about taking her students to The Valentine each school year. It’s a field trip she books well in advance.

“I think kids have an opportunity to relate to The Valentine because of what they learn in school,” says Christian, who taught third and fourth grades at Oak Grove-Bellemeade Elementary School and is now teaching second grade at Barack Obama Elementary School. “The kids are interested because The Valentine makes history come alive.”

Kids are able to view authentic artifacts, interact with materials, and explore the galleries during their visit. “This is a special museum that is diverse. Kids can see themselves here and see why Richmond is such a historical place,” says Christian, who participated in the Teacher Fellowship Program as an education fellow at The Valentine this past summer.

The Valentine is an important stop for students and families because it tells the stories of Richmond, she adds. “The Valentine continues to explore fresh ideas to connect with anyone who comes through the doors.”

More Than a Century of Serving Students

The Valentine has been dedicated to public schools and education for the past 122 years. “We have been free for every Richmond public school since 1902,” says Bill Martin, the museum’s director, noting the museum is celebrating its 125th anniversary this year.

Students visiting the museum come from Richmond and surrounding counties to learn more about Richmond history. “History in school can sometimes feel like a boring subject,” says Liz Reilly-Brown, director of education and engagement at The Valentine. “We want people to see themselves in history today and to connect their lives with the stories of the past that kids are learning in school.”

The Valentine facilitates school field trips to its museum as well as classroom visits from museum staff. “We realized not every single school and age of student can come here, so we support teachers by coming to the classroom and bringing hands-on artifacts. We customize the programming a lot. We try to amplify what the teacher has been teaching in the classroom,” says Reilly-Brown.

The museum’s multi-visit, project-based learning program meshes student visits to The Valentine with staff trips to the classroom. “Students get to lead the project,” Reilly-Brown says. “If their interests are driving the research question, that will help them become creative thinkers.”

At the museum, students participate in interactive experiences, especially in the “Hands-on Stories Room” in the Wickham House where kids can learn about four of the people who lived in the house in the 1800s – Cary and Elizabeth Wickham, who were two of the Wickham children, and Robin Brown and Amy Green, who were two of the enslaved people who worked in the home – through the authentic items in four boxes.

One of the boxes contains items from a child who lived in the home. Students can learn more about growing up in the house by seeing and holding the toys, a piece of clothing, or a school item such as slate, chalk, or a book.

Student visitors learn the history of the Wickham family, including the realities of urban slavery. They see history through the eyes of an upper-class Richmond family.

“The objects we have from people who were enslaved in the home help ground the kids in real life,” Reilly-Brown says. “One of our favorite things with older students is giving them the opportunity to look at primary sources like newspaper articles regarding events such as the Great Depression or the first walk on the moon.”

The Valentine is not always thought of “as a go-to place for kids, but if you look at the numbers, kids are the largest segment we serve,” Reilly-Brown says.

125 Years of Storytelling

The genesis of The Valentine dates back to the collections Mann Satterwhite Valentine amassed in the late 1800s. In 1882, he purchased the Wickham House (a National Historic Landmark built between 1812 and 1815) and dedicated one room to those collections. When he died in 1892, he left his collection, along with the Wickham House and a $50,000 endowment, to establish a public museum in his name. The Valentine Museum officially opened six years later on November 21, 1898.

One of the keys to the museum’s longstanding success is its dedication to being “useful to this community,” says Martin. “We are smaller in scale than many other museums. We have the ability to take an unusual perspective to understand a quirky element of our history. We are about serious business, but always with a sense of irony about the work.”

If there’s one thing that Christian, the teacher fellow, respects about the museum, it’s that it “doesn’t sugarcoat history. It’s not afraid to dive deep into Richmond’s history,” she says.

Sharing the story of Richmond – the good and the bad – through its past always generates discussion. It’s the energy around those conversations “that motivates us,” Martin says. “It’s about the great things Richmonders have done and also about the horrors of our past. The things between those two stories create energy for the future.”

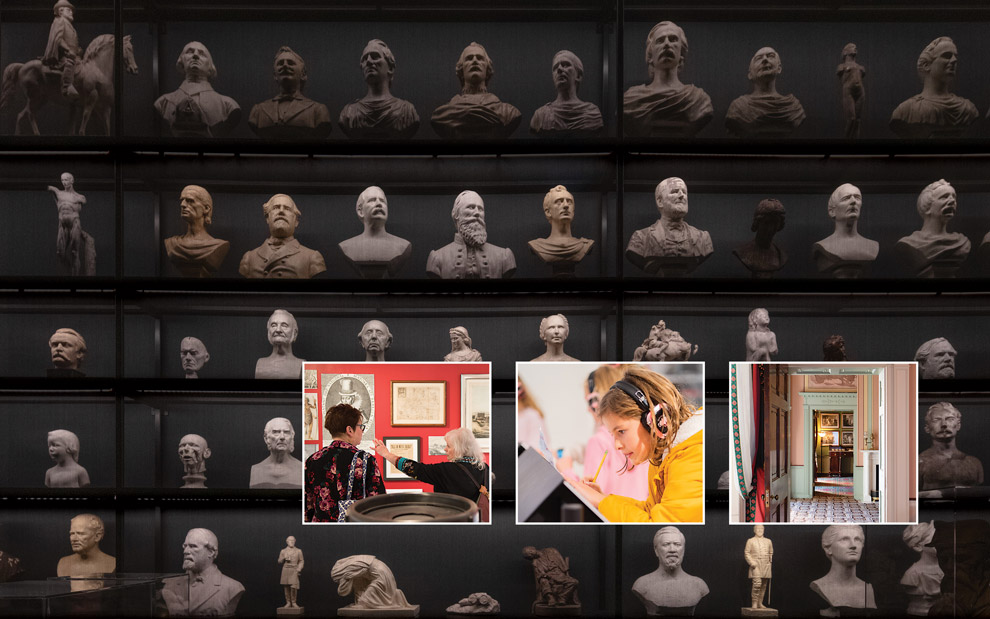

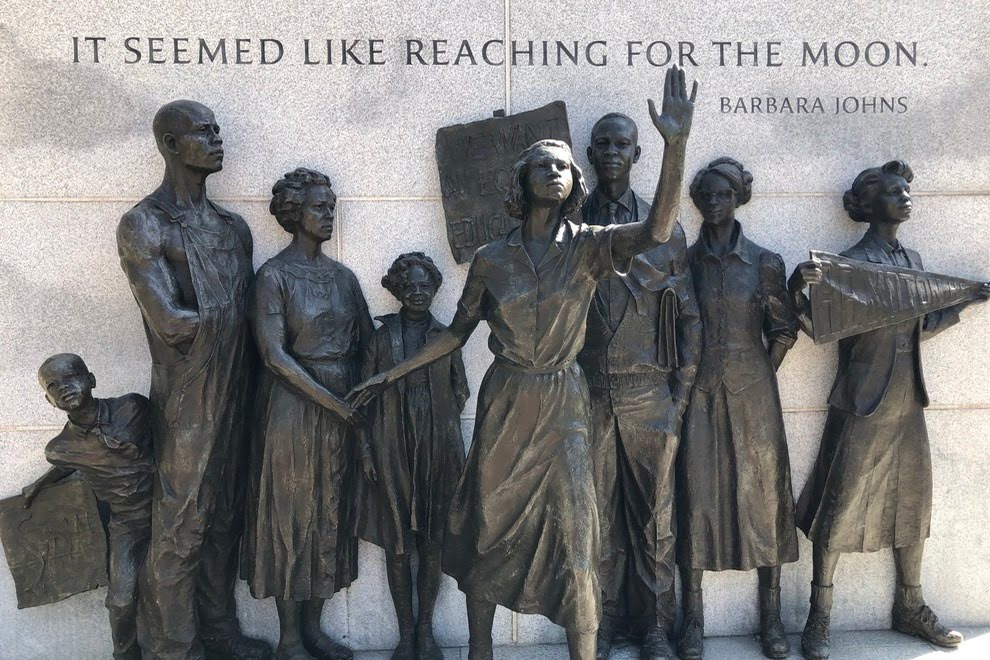

Sometimes the stories told at the museum can be difficult to communicate in a way that connects people. One example is the exhibit “Sculpting History” in the Edward Valentine Sculpture Studio. The exhibit asks three questions: How does fiction become an accepted truth? How can someone believe a lie? How do history and art influence politics and power?

The multimedia exhibit, which opened in January, uses the sculptures of Edward Valentine as well as documents, objects, images, quotations, and questions to examine the Lost Cause myth. The Lost Cause was a campaign to convince the public of three things: 1) the Civil War was fought to protect Southern states’ rights, not the institution of slavery, 2) that slavery was a beneficial social structure for both enslavers and the enslaved, and 3) the South’s role in the war was not a treasonous act against the United States.

“The story of Richmond is really important,” says Martin. “This institution has a particular perspective on the world and history and how we have evolved. It’s totally in character for who we are as an institution to be continually looking at ourselves for the biases and opportunities we have. Richmond has a Civil War history, but for The Valentine it’s the broader, richer story that is at the core of what we do.”

Christian’s students “are amazed by it,” she says about the Sculpting History exhibit. “The Valentine is not afraid … of history. Parents need to have conversations with their child, have an open dialogue. [Viewing the exhibit] might help parents in explaining things that happened in the past.”

Presenting an authentic experience for visitors is at the core of the museum’s philosophy. “We can look at how things have changed and how they are the same,” says Reilly-Brown, noting that everything, including history, has become more political. “One thing we do as an institution is try to be really open to conversations and differing opinions. It’s okay to have different opinions. We want people to feel heard and to give us feedback.”

Collecting and Displaying History at The Valentine

In the last five years, The Valentine has been in the midst of a huge renovation to its collection area in order to provide the best care of and access to its collections. “It’s our biggest project ever,” says Martin. “We had to move our collections to an off-site location so we could renovate [The Valentine space] to provide the ultimate storage facility.”

All of the archives are now back in-house with greater access for scholars and researchers than ever before. The museum has added a staff member to help assist researchers with their needs.

“We encourage anyone doing research to take an extra step to research the treasures we have made available that have never been available before,” says Martin, adding that not all research has to be conducted online.

The museum has also renovated its reading room, making it more accessible for researchers, and added a viewing room that provides a space for classes to work on object-based projects.

Thanks to the new, large, state-of-the art cabinets in the temperature-controlled storage space, the museum has a more comprehensive understanding of its collection.

“There will be new things that have not been exhibited by The Valentine because we have discovered things in our collections,” Martin says. “Our exhibitions will have a broader range of objects.”

In looking at its collection, the museum has determined not only what it has, but also what is missing, and the diversity of the collections is enormous. It ranges from the 1800s to the present, from textiles to photographs, from stories of slavery and enslaved people to stories of freedom, from The Valentine family to iconic Richmonders, such as Donnie Corker, also known as Dirtwoman, Santa and the Snow Queen, and civic leader and philanthropist Mary Tyler Freeman Cheek McClenahan. One of the museum’s newest collections highlights portraits from Style Weekly’s archives. “It’s a nice mix of profound remembrances and some fun quirky moments,” says Reilly-Brown.

The museum now has the capacity for new objects from Black and immigrant communities in Richmond, which Martin says had not been well represented in the past. “When you know what you have, you can identify stories and objects that are missing,” Martin says. “We want to make sure we have space for them and add the stories that are underrepresented.”

To better serve history tourists and out-of-town guests, The Valentine was recently added to the official Richmond visitor center lineup. “We made modifications to meet the requirements of the Virginia State Visitor Center,” says Martin, noting that parking is free in The Valentine lot. “We are very excited. We feel like there are an amazing group of resources located downtown. Folks just need guidance in what to see and where to go. Our staff is already doing that.”

Amazing Space for Families

In addition to its impact on schools and students, The Valentine is a hidden gem for all families.

“If [families] are looking for an experience that has less sensory overload or is quieter, The Valentine is a good choice,” says Reilly-Brown. “We have activities like scavenger hunts, and they can tour a historic home. We have ways that people who learn differently can learn about history and experience The Valentine.”

The museum also conducts walking tours of the city, highlighting everything from Hollywood Cemetery to Carytown with a focus on LGBTQ+ history. Tours are free for children under eighteen. “Getting out and using your body is an impactful way to learn,” says Reilly-Brown.

No one knows that better than Hanover resident Victoria Zemlan, her husband, and their two young energetic sons, who all enjoy events and activities outdoors.

One of their favorite events is Winter Wander, held at The Valentine in December to celebrate the winter holidays in the city’s Court End neighborhood. “The kids get to walk around and get their energy out,” Zemlan says. “The event has music, hot cocoa, vendors, and activities. One year they were in the courtyard doing crafts. One person handing out bags gave the kids bags with everything needed to make pipe cleaner critters, including bells.”

When they go inside the museum, Zemlan’s boys get to wander around the exhibits. “I’m surprised at how interested my kids were in the displays. It’s great to see them get interested in the same kind of things that interest me,” she says.

When Zemlan and her husband were dating, they often participated in the tours The Valentine offers. “I would like to bring my kids to those, too,” she says. “The Valentine has a special place in my heart as a longstanding keeper of Richmond history.”

Martin, who has been at the helm of The Valentine for thirty years, says that kind of family review is exactly what The Valentine is working to receive. “We are all Richmond, all the time,” he says. “We love our city, we love our history, and everyone should make time to visit The Valentine.”