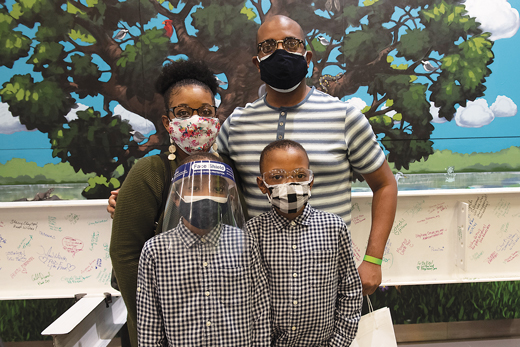

LaToya Cypress and her husband Brett keep a bag packed in case they have to rush to the emergency room with one of their twin sons.

“We are pretty much in a ready-to-go situation,” says Brett. “It’s like a new normal. Other kids get fevers and parents can treat it with Tylenol. We are automatically going to the ER. It’s just what we do.”

The couple’s 12-year-old sons, Gabriel and Noah, were born with sickle cell disease, an inherited group of blood disorders.

“In patients with sickle cell disease, instead of having red blood cells that are smooth and round, these patients have red blood cells that are a sickle shape and are hard and sticky. These sickled cells do not last as long in the body, which causes chronic anemia. They get stuck in the vessels which causes pain and they damage blood vessel walls, which over time, can lead to organ damage,” says Nadirah El-Amin, DO, with the Children’s Hospital of Richmond at VCU (CHoR). “Patients with sickle cell disease can have complications from the top of their heads to the tip of their toes.”

Sickle Cell Disease Is Genetic

Sickle cell disease affects about 100,000 people in the United States and is most common in African Americans or people of African descent.

“It is the most common inherited disease worldwide,” Dr. El-Amin says. “It occurs in about one out of 365 Black or African American births and about one in every 16,300 Hispanic Americans in the U.S. About one in thirteen Black or African American babies is born with the sickle cell trait.”

Sickle cell is a genetic disease. LaToya knew she had the sickle cell trait, but when the twins were born, the couple didn’t know that Brett also carried the trait.

LaToya and Brett didn’t know their twins had the disease until about a week after their birth. Doctors discovered it after a routine test given to all newborns.

Even though the call from the pediatrician was shocking to the couple, they wanted to keep a positive attitude. “I had knowledge about the disease because I have the trait,” LaToya says. “We wanted to maintain being hopeful and in spite of the disease, they would be fine.”

The couple immediately set up an appointment with a pediatric hematologist at CHoR. At the time, the twins were not having any symptoms related to sickle cell.

“You don’t usually see symptoms until about nine months. The ninth month, one of our sons started with a fever of 103 degrees. It came out of nowhere,” LaToya says. “Any fever they have is an automatic emergency room visit. The first fever was a two-day hospitalization for one of them and a few days later, the other [had a fever] because they are twins and like to share everything.”

Going to the hospital with fevers and/or colds became a routine ritual. As the twins approached their one-year birthday, they began experiencing the pain associated with the disease.

“We had to have a keen eye on them. They weren’t old enough to know what was happening,” says LaToya, noting they would look for little cues that marked pain, like one of the boys crawling but not being able to use one of his arms in that process.

Some of the common symptoms that people with sickle cell experience are anemia or low red blood cells, for which patients may need transfusions. Painful episodes can last for hours to several days and can require opioids or even admission to the hospital for pain management. Other complications include gallstones, enlarged spleen, stroke, and kidney damage.

“Sickle cell has so many different faces to it,” LaToya says. “There are different organs that are affected. It can even affect your eyesight.”

The symptoms their sons have are “followed by several different specialists,” she adds. “It’s a collaborative effort.”

Her sons symptoms differ, she adds. “One of my sons has more pain than his brother. Early on, the twins had more colds and fevers. Now, they have more pain and related crises.”

She remembers lying in bed and waking abruptly at two or three in the morning by one of her sons screaming in pain. “There is only so much you can do for alleviating the pain,” she says. “It’s hard being a parent when you go to the hospital and know that they are still hurting. Faith plays a role in our strength, and having a good support system is a blessing. We have a great medical team as well.”

LaToya has a brother with sickle cell anemia and a cousin with the disease. “Both have been tremendously helpful throughout the years and I consider them advisors,” she says. “We are grateful to have people close who can directly relate to the boys’ experiences, encourage them, and provide tips on managing the challenges of having sickle cell.”

Why Donating Blood Matters

There are times when a person’s sickle cell disease is very active and their body is “breaking down their red blood cells at a very fast rate, such that their hemoglobin will drop down to a dangerous level,” Dr. El-Amin says. “It is during these times that the patient may need a [blood] transfusion to help them feel better.”

Dr. El-Amin added that some patients who have either had a stroke or are at a high risk for stroke are on a chronic transfusion program and receive blood transfusions monthly.

Every sickle cell patient is affected by the disease differently. For example, some patients may only need one transfusion in their lifetime and others require monthly transfusions for the rest of their lives. “Blood transfusions for many of our patients can be life-saving,” Dr. El-Amin says.“Because of that, we always need willing blood donors to help support this population. In addition, we know that sickle cell patients benefit from donors who are of a similar race or ethnicity. We always try and encourage everyone to donate, but also strongly encourage people of different racial or ethnic backgrounds to donate as well.”

It’s important for blood types to match as closely as possible when there is a blood transfusion. “In addition to blood type, there are actually a lot of proteins in blood that ideally would be matched to prevent a dangerous reaction,” Dr. El-Amin says. “That being said, the blood donation does not have to be

from family, it can be from anyone who matches the patient’s blood type.”

Living with Sickle Cell Disease

Because sickle cell is a lifelong disease, CHoR treats patients from birth to eighteen years of age, at which point they transition to the adult sickle cell program at VCU Health. Recognizing that the transition from pediatric to adult care can be challenging for families, CHoR has developed a program to help ease that transition as much as possible.

“We educate our patients about transition from an early age, but really start ramping up our efforts around high school,” Dr. El-Amin says. “At each visit, we review with our patients their health history, we encourage them to be in charge of their medications, to learn to set appointments, and to become advocates for themselves. Our social workers meet frequently with our transition-age patients to assess readiness for transition, and we discuss as a team where we need to best focus our efforts for each patient.”

In addition, the hospital hosts an annual retreat for transition-age patients to help reinforce their understanding of the disease.

“The adult patient navigators will come to the transition-age patient’s appointments to get them used to some of the team members on the adult side so that when they do transition, it is not all unfamiliar,” Dr. El-Amin says. “We also engage in quality improvement work around transition so that our transition program continues to grow and develop into something that

best prepares our patients to become adult patients with sickle cell disease.”

There are now curative options for sickle cell such as bone marrow transplants. Curative gene therapy is also being studied, and “has shown great promise of curing patients of their sickle cell disease,” Dr. El-Amin says.

At twelve, Gabriel and Noah have not begun the transition phase yet, although the family has met with Dr. El-Amin.

Parenting and Sickle Cell Disease

COVID-19 and its variants have added a new layer of concern for the Cypress family, but the pandemic has not changed the family’s habits drastically.

“We have been exercising precautions for twelve years,” LaToya says. “We didn’t have to do a lot of adapting. When they first started school, there was an increase in hospitalizations. At one point, they didn’t go a full week of school together until February of the school year. We always had this caution. When it comes to germs, we are always being a little more cautious. We were also social distancing to a degree before COVID. We have increased what we were doing, but it wasn’t a big shift.”

The couple’s main goal for their sons is to live as normal a life as possible.

“Our desire is for both of our sons to recognize and know their bodies; to know how to take responsibility for how they are feeling,” Brett says. “The more they are educated about their bodies gives them power and puts it in their hands. We believe the more proactive they are with sickle cell, the better.”

Photos: Courtesy VCU University Marketing, Kevin Morley, Thomas Kojcsich, and Scott Schwartzkopf