Jay Grymes was first introduced to the Violins of Hope when he helped coordinate the exhibit’s visit to Charlotte, North Carolina in 2012. The touring exhibit tells the remarkable stories of violins played by Jewish musicians during the Holocaust.

Grymes, author of Violins of Hope: Violins of the Holocaust – Instruments of Hope and Liberation in Mankind’s Darkest Hour, recognized that for most violinists, playing the instrument is a passion that brings them joy. In certain circumstances – like during the Holocaust – the violin can determine whether you and your family live or die.

“When I started writing [the book] my main goal was to show a different side of music and how it can function in different ways,” says Grymes, PhD, a professor of musicology at University of North Carolina at Charlotte. “It can be used as a form of torture or a solution to keep a family alive. What I learned and what I hope people take away is the diversity of experiences during the Holocaust. Each chapter tells a different story.”

The book shares the stories of some of the violins that are part of a special exhibit and programming in Richmond. The exhibits are scheduled through October 24 at the Virginia Holocaust Museum, the Virginia Museum of History & Culture and the Black History Museum & Cultural Center of Virginia. Each museum will showcase several violins from the exhibit as a loaned display.

Special concerts by the Richmond Symphony on September 9 at Cathedral of the Sacred Heart and on September 10 at St. Mary’s Catholic Church (both of which have sold out) are featured events during the exhibit’s run. A third concert has been added on September 12 at Dominion Energy Center. Members of the Richmond Symphony will play some of the Violins of Hope during the concert. Information about tickets for the September 12 concert is available on violinsofhoperva.com.

The Instruments Have a Voice

“The instruments in the Violins of Hope collection make beautiful museum pieces, as those who see them at the Virginia Holocaust Museum, the Virginia Museum of History and Culture, and the Black History Museum will discover. But the heart of the project is that the instruments come alive again during performance,” says Grymes. “Although some of the musicians who once owned the instruments were silenced by the Holocaust, their voices and spirts live on when their violins are played.”

Gyrmes is fortunate to have heard the violins played many times and has listened to the performer’s perspective on playing the violins.

“Violinists tell me that the fingerboards of old violins can have small indentations from how their previous owners played them. This allows modern performers to form a connection with an instrument’s history that is not only spiritual but also tactile,” he says.

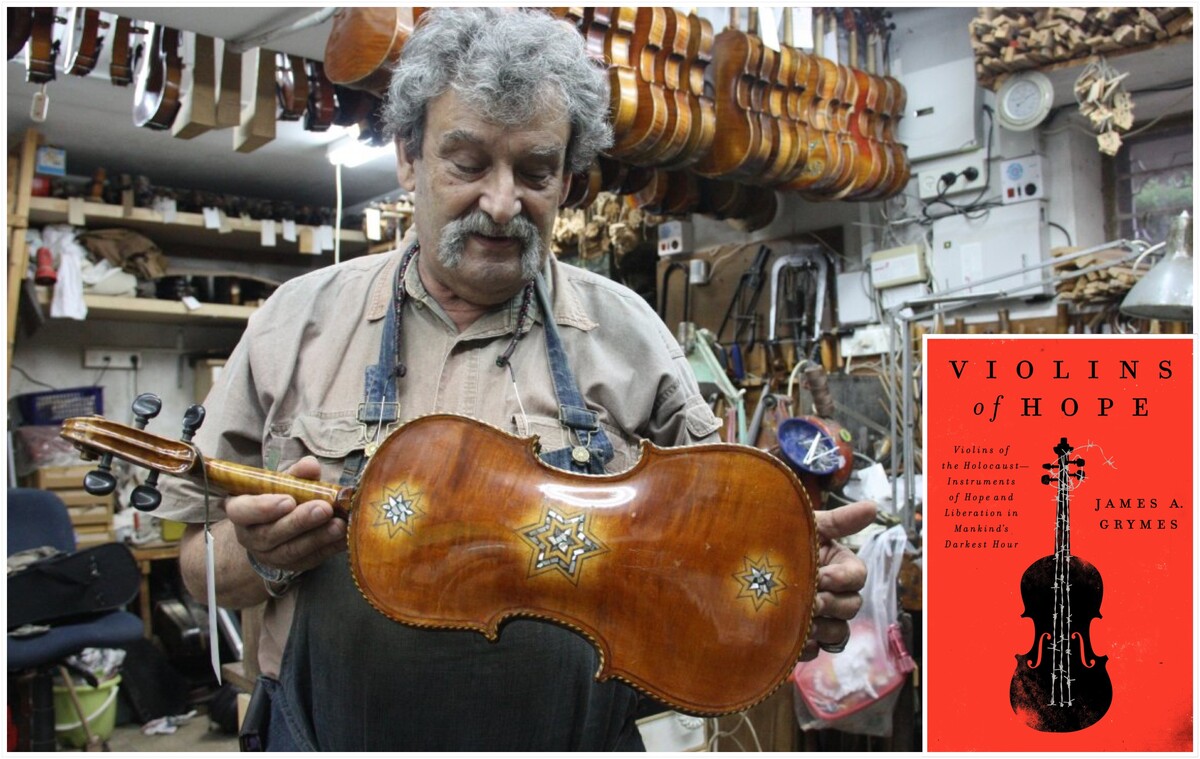

The 60-plus violins sent to Richmond (nineteen are on display at the museums and the rest will be played in concerts or used in educational programs) were recovered and restored by Amnon Weinstein, an Israeli violin shop owner and master craftsman who lost 400 family members in the Holocaust.

Grymes, a Richmond native, traveled to Israel more than once to meet with Amnon and spend time in his shop. Those visits, where he heard the stories of the survivors as well as Amnon’s story, inspired Grymes to write his book.

“The Holocaust is not a single story of 6 million Jewish deaths. It’s a story of 6 million individual deaths. I tell the stories of six of the violins and of Amnon,” he says.

The Stories Live On

Amnon grew up in post-Holocaust Israel. His parents fled the country and in doing so, had lost contact with their family members. After the Holocaust, the family learned that 400 family members had been murdered.

“Amnon grew up in a household where grief and loss permeated their lives, but they could’t talk about it,” Grymes says. “When he started thinking about the role the violin played in Jewish lives, in a way, he could connect with his own family’s history. It’s really interesting, the confluence of things. Amnon is one of the best violin makers in the world. There are only a few that could do the restoration he does. It’s something quite special.”

One of the survivor stories that haunted Grymes was that of Feivel Wininger, a violinist from Romania. He and his family were sent on a death march during the winter to the territory of Transnistria. His uncle and his mother died. His infant daughter, Helen, who was nine months old, was growing weaker and weaker.

Because he played the violin he was able to leave the ghetto and perform at parties for the Nazis. He would bring home any leftovers of food back to the ghetto. By doing this he could sustain himself and sixteen friends and family members through the Holocaust. Feivel’s violin, which he called Friend, understandably, became part of the family.

“As a new father myself, I couldn’t help thinking about that burden,” Grymes says of Feivel’s journey to the camps. “My own daughter was nine months old at the time [I was writing the book]. That was pretty emotional for me.”

He hopes the stories in the book, like Feivel’s, will help humanize “the tragedy,” he says of the Holocaust, adding that Feivel’s violin can be viewed at the Virginia Holocaust Museum.

Helping Families Stand up to Hate

“James Grymes is a fantastic author and musicologist,” says Sam Asher, executive director of the Virginia Holocaust Museum. “It’s so brilliant how he writes about the Violins of Hope. I don’t think anyone tells the story better than he does. We use a lot of the stories he wrote about in the book.”

Asher is excited that the Richmond community will get to see and hear the violins as well as the stories of the Holocaust.

“Violins of Hope provide us with the understanding that good things come on the other side of a pandemic like they did at the end of the Holocaust,” he says. “It is going to tell the stories of what happens at the end of the long tunnel — there is hope. The Violins of Hope exhibit lets you see the hope. It brings us out of a very dark time.”

Learning what happens when “hatred goes unchecked” is important, he says.

“You see how people’s lives and countries can be totally destroyed. We, as a democracy, have to be on the look out and stand up against hatred, bigotry and anti-Semitism when we see it,” says Asher.