If there’s one takeaway Virginia Indians want you to glean from this article, it is this: We are here.

To this day, I have people say to me that they didn’t know there were Indian tribes in Virginia or reservations,” says Chief Mark Custalow of the Mattaponi. “We haven’t gone anywhere. We want people to know we are here.”

Hollywood is partly to blame for this misconception. “Because of movies and television, people think the only Indians are on the other side of the Mississippi,” says Custalow.

People are also more aware of Indians of the American West (often more broadly referred to as Native Americans), because their path to federal recognition was easier, as “a result of their treaties with the United States government,” says Reggie Stewart, second assistant chief of the Chickahominy. “So, even though the Virginia Indians were the first to make contact [with Europeans], their path to federal recognition was more difficult, due to the fact that their treaties were with England.”

The majority of the blame, however, can be found in Virginia’s history with the passing of the Racial Integrity Law in 1924. After passage, the Virginia Bureau of Vital Statistics recognized only two races – white and black. If you were a Virginia Indian, you didn’t exist, according to the law.

Dr. Walter Plecker, registrar of the Bureau of Vital Statistics in 1924 and a white supremacist, made sure “doctors, nurses, and midwives understood that they were to enter a race of white or colored on a birth certificate, or there would be consequences,” says Stewart. “That reinforced the segregation and discrimination in Virginia. It was a form of document genocide for the Virginia Indians.”

The law also forbade interracial marriages. “My parents had to go to North Carolina so they could have Indian on their marriage license,” Stewart says. “Some people went to Washington, D.C.”

Starting in the early 1900s, Virginia tribes began establishing their own schools. Children from the Chickahominy and Chickahominy East attended the Samaria Indian School in Charles City County, and children from the Upper Mattaponi attended Sharon Indian School in King William County, which now is the only public Indian school building still standing in Virginia. It is listed on the Virginia Landmarks Register and the National Register of Historic Buildings.

A Kindred Spirit

When it comes to Virginia’s first Americans, there can be confusion as to whether to refer to the tribes as Virginia Indians or Virginia Native Americans. “Even if you ask Indians, you get a different answer,” says Stewart. “First it was Native American; then the trend was American Indian. Either one is appropriate.”

Stewart believes Virginia Indian is appropriate. Others have no preference or prefer Virginia Native American.

Being proud of one’s Virginia Indian heritage is more than just having a certain bloodline. “It’s the culture,” says Stewart. “It’s not just to whom you are related.”

The Indian community in Virginia is close-knit. There is a strong community camaraderie that is far more united in spirit than our country is today, according to Stewart. Much of that stems from the willingness to share and interact. “It’s that you went to church – a huge part of the Indian culture is going to church,” says Stewart. “When there were revivals in the summer or homecomings, the members of churches would go to other churches to visit. That created a relationship between the tribes early on. The church was the center

of the tribe.”

Annual pow wows bring tribal members “back home to visit with friends and relatives,” says Chief Frank Adams of the Upper Mattaponi. “It also brings tribes together. Young people get to meet other teens in other tribes and they get to connect.”

Adams is constantly surprised by the number of people in Central Virginia who don’t know how many tribes are “active and accounted for in Virginia and just how close-knit we really are,” he says.

There are eleven tribes in Virginia: Mattaponi, Pamunkey, Chickahominy, Eastern Chickahominy, Rappahannock, Upper Mattaponi, Nansemond, Monacan Indian National, Cheroenhaka (Nottoway), Nottoway, and Patawomeck. There are two reservations –Mattaponi and Pamunkey – both in King William County. They are the two oldest reservations in the nation.

Clearing Up Misconceptions

Often, people visiting the Mattaponi reservation have the idea that tribal members live in teepees and longhouses like their ancestors. “We have homes like everyone else does,” Custalow says. “People think you have to dress the part all the time.”

Some of the tribe’s members who live on the reservation do live off the land – hunting and fishing and the like – but most members work in jobs around the state, and are no different than the average Virginian.

There is also the misconception that all tribes live on reservations, “have casinos and are wealthy. That we have this built-in economic development infrastructure where there’s money flowing into the tribe,” says Stewart. “That couldn’t be further from the truth. A lot of times, reservations are on land that’s not wanted by the government; land that’s far away from population centers. That makes it difficult for members of the tribe to get jobs and an education.”

Across the country, says Stewart, there are many instances where reservations depend on government funding to sustain the tribe. That can breed a culture of dependence and “lend itself to substance abuse. It’s a sad situation. It’s poverty, and people don’t understand that,” says Stewart, who emphasizes that this does not apply to the Mattaponi and Pamunkey reservations.

Federal Recognition

For years, Virginia tribes have tried to get federal recognition. At times, it seemed like an unattainable endeavor. “It was a 20-year process. It was an ongoing process with no end in sight,” says Adams.

What exactly is federal recognition? “It’s recognizing the sovereignty of each tribe. Recognizing the tribes for who they are,” says Stewart. “It provides access to funding and federally funded programs that are only available to federally recognized tribes.”

For example, scholarships and grants are available to members of federally recognized tribes who are going to college. Those funds are specifically earmarked for federally recognized Indians. “These scholarships and grants are competitive, and there is a selection process. Now our members going to college can apply for those,” Stewart says.

The Pamunkey received federal recognition in July 2015. The tribe began the process to petition the Department of Interior for recognition in the early 1980s. “The petition process basically required that we show continual existence as a functional tribal government and social group since historical time,” says Chief Robert Gray of the Pamunkey, adding the tribe is “eager to move forward post-federal recognition in a way that benefits our members and our neighbors.”

The Chickahominy – along with the Chickahominy Eastern Division, Upper Mattaponi, Rappahannock, Nansemond, and Monacan tribes – received federal recognition this past January. The organization that headed this process was the Virginia Indian Tribal Alliance for Life (VITAL), which was formed to lobby the U.S. Congress to sponsor the bill for federal recognition. It included representatives for the six tribes along with the assistance of Indian activist, Thomasina E. Jordan.

“That organization embodies the cooperation among the tribes in Virginia. It shepherded activities, fundraisers, and trips to Washington, D.C., to speak to the Virginia delegation and other members of Congress,” says Stewart. “They testified during hearings on both the House and Senate side to build support. It’s another example of Virginia tribes working together.”

The day the six tribes became federally recognized was a historic day in Virginia. “The normal citizen doesn’t have a clue how important that day was,” says Adams.

Other tribes that have state recognition are the Mattaponi, Patawomack, Nottoway tribe of Virginia, and the Cheroenhaka (Nottoway). The Mattaponi tribe began working on a federal recognition letter of intent in 1984. “We are going through the Bureau of Indian Affairs for the process,” says Custalow. “We are finishing up phase two, and then we go into phase three.”

With federal recognition, the tribes will be able to improve living conditions for tribal members by tapping into specific funding and programs earmarked for federally recognized tribes. Funding also helps the tribes build out their infrastructure and hire staff who can “help operations and drive work in a better manner,” says Stewart.

The complicated funding application process is like “starting a business,” he adds. “We are now in that process. In most cases, for any funding you are planning to pursue, you have to develop a specific business plan as to how you intend to use those monies. If you are awarded the money, you have to provide periodic reporting to demonstrate how you are utilizing those funds.”

The process can become a difficult balancing act. “It’s a lot of work to just apply for the funding, much less manage it once you receive it,” Stewart says. “It’s not free money.”

But the eventual payoff of federal recognition is worth the struggle and the paperwork. “It means a lot of opportunity. Each tribe can make a decision to go as big or as small as you want to,” says Adams.

Honoring the Past

The history of the tribes reflects a deep-rooted connection to this land. The tribes located in central Virginia – the Mattaponi, Pamunkey, Chickahominy, and Upper Mattaponi – are Eastern Woodland Indians, part of the Algonquin family of Indians.

“The Pamunkey Indian Tribe has existed in what is now Eastern Virginia for over 10,000 years,” says Gray. “We are the tribe of Powhatan and Pocahontas. We have continued to maintain a portion of our ancestral homeland since that first contact with Europeans at Jamestown. Our people have fought in every American war from the Revolutionary War to the present war on terrorism. We have persevered through centuries of racial discrimination but have maintained our land and identity to the point of recently attaining federal recognition.”

The Pamunkey reservation dates back to treaties with the Crown of England in 1646 that were reaffirmed in 1677. The tribe has a total enrollment of approximately 400 with about fifty-five tribal members residing on the reservation.

The Mattaponi reservation was confirmed in 1658 with land granted by the King and Queen of England. Out of its approximately 2,000 members, sixty-five live on the reservation. The tribe has a museum and a trading post, open to the public by appointment. It also has a fish hatchery. “When we are fishing for shad, we put the fry [baby shad] back into the water after they hatch,” says Custalow.

Each year around Thanksgiving, the Mattaponi and Pamunkey honor the 1677 Treaty of Middle Plantation by carrying the first thing from its forest or waters to the Governor. “At first the Treaty called for twenty beaver skins per year,” says Custalow. “We’ve kept that tradition for over 300 years.”

Virginia Indians are passionate about preserving their culture and their traditions. “It’s important to hold onto who you are,” says Custalow. “Our role is to help people practice our culture and teach it to the ones coming up.”

Mentoring the Next Generation

Mentoring the Next Generation

In the Indian community, it’s customary to pass along the culture and heritage to the younger generation by mentoring kids as early as possible. Young members of the tribe learn about their native heritage as well as native dances. Two young people mentoring youth in their tribe are my late husband’s granddaughters, Rachel and Emily Tupponce. Both are proud members of a community their late grandfather, Reggie, a member of the Upper Mattaponi tribe, respected and participated in. And, he certainly was proud of them.

“Since I am a descendent of both the Chickahominy and Upper Mattaponi tribes, I feel like I am a member of many families in the Indian community,” Rachel says. “Wherever I go, there are people who knew me before I was even born!”

Both college students are jingle dancers who dance at pow wows around the state. “This type of dance is a healing dance,” says Rachel. “There are times when jingle dancers are asked to dance for someone who is sick. It’s like a prayer for them.”

Rachel enjoys teaching younger girls how to dance because it’s “important that the younger generations carry on our tradition,” she says.

Emily is concentrating on teaching the next generations “the importance of what it is to be native,” she says. “They need to know how to properly and respectfully dance, as well as have respect for the dance circle, their regalia and feathers, and our traditions.”

She always carries herself in a respectful manner, she says, because “I am a role model for the young girls in my tribes,” she says. “I make it my mission to teach native youth about the significance of being proud of who they are and telling their story to others.”

Some of the biggest lessons Rachel’s family have taught her are to respect her elders and “care for and protect the earth and keep the traditions alive,” she says.

Virginia Indians are a “huge part of our state’s history,” Emily adds. “We are still here and will continue to grow and thrive as sovereign nations for generations to come.”

A Place to Reflect and Remember

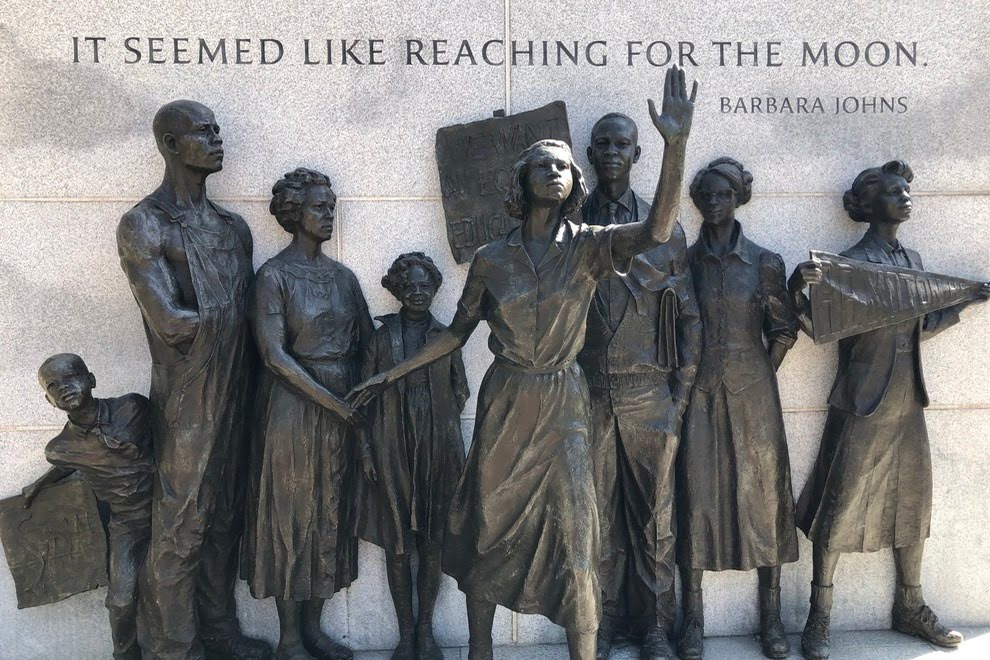

This April, the Virginia Indian Commemorative Commission and the Virginia Capitol Foundation, along with Governor Ralph Northam, dedicated Mantle, a monument recognizing the lasting legacy and significance of American Indians in the Commonwealth.

The Virginia Indian tribute on Capitol Square serves as a meditation space where visitors can either walk the labyrinth or sit and contemplate. It reflects the positive values that set Virginia Indians apart from other cultures.

“The goal of the monument is to recognize the Virginia Indian tribes’ lasting legacy and significance, as well as to ensure that the rich and inspiring stories of our native peoples will endure,” noted Delegate Christopher K. Peace at the monument’s groundbreaking.

Mantle features a 5-foot wide winding footpath that follows the outline of the monument, rising from and returning to the earth. In addition to the path, there is a continuous, smooth stone wall, which serves as a bench.

“I have to give kudos to our past Chief Ken Adams who approached Delegate Peace with the idea of a monument to recognize Virginia Indians, worked to get the project started, and saw it to the end,” says Chief Frank Adams of the Upper Mattaponi. “I think it’s long overdue and a much welcome site to all Virginia natives.”