Three years ago, Kat* was having a fairly typical seventh-grade experience at her Henrico County middle school. She got good grades, enjoyed a close group of friends, and was thinking about trying out for the softball team.

She especially looked forward to her school’s spring theatre production. She had recently added drama to her long list of creative interests and was excited to perform in the show.

But this was March 2020. On what would have been opening night, the production was abruptly canceled, along with school itself, while the nation came to grips with the growing coronavirus pandemic.

Kat says it was the beginning of a very tough time for her. Online learning proved difficult, and as an extrovert, she struggled with the sudden isolation.

“I was depressed about not seeing my friends,” she says, “and I wasn’t able to do any of the things that made me happy, like dance class or theatre.”

As time passed, and the initial two-week closure of schools became a long-term arrangement, Kat went on walks to clear her mind. She eventually found a new group of friends and discovered a dangerous pastime.

“I was fourteen when I smoked [weed] for the first time,” she says. “And it didn’t seem like a big deal at first. I didn’t really get all that high.”

In the beginning, she says, the high wasn’t as appealing as the camaraderie that came with it.

“It was just an easy thing to do for me to feel less isolated,” she says. “Because, you know, if I wanted to hang out with somebody, I could be like, hey, do you want to go smoke together? And then the walks ended up just being times when I could pick up drugs.”

Her experimentation escalated when Kat was at home, alone and bored. She discovered opiate painkillers and quickly lost control.

“I just thought it was something I was just doing because everybody did it,” she says. “I knew that my substance use was causing problems in my life, but I didn’t realize yet that it was going to be the main problem.”

Things came to a head late one night in February of 2021, when Kat’s parents found her extremely intoxicated.

“It was scary,” says Carrie, Kat’s mother. “We didn’t know what she was on, and we were trying to decide if we should take her to the ER or what.”

Carrie says she was surprised to hear the clearest direction come from Kat herself.

“She said very clearly, ‘I need help,’” Carrie says. “That has really stuck with me – her looking at me with tears in her eyes, drunk and high at 2 a.m. and saying, ‘I need help, please take me to a mental hospital.’ It gave me the strength to do something, because if she can be brave enough to say that, and recognize that, we have to give it to her.”

After some Googling, Kat’s parents found the quickest path to the help Kat was asking for was through the ER. From there, Kat was transferred to Tucker Pavilion for a nine-day stay. Doctors there determined that she was dealing with depression and anxiety, and believed the drug use was less of a concern.

“Their initial thought was that she didn’t have a strong addiction issue because she wasn’t begging to get out of there,” says Carrie. “So they told us to keep an eye on her, drug test her regularly, and if this comes up again then we need to talk about treating it.”

Over the next few months, Kat’s parents watched her closely for signs of trouble. Eventually it became clear that Kat was using again.

“I was using it to numb out. I guess that’s the best way to put it,” says Kat. “And then eventually it wasn’t something I was doing to make myself feel better. It was something I was doing to just feel okay.”

Kat’s parents enrolled her in a residential treatment program in Chicago. After that stay, she returned to Henrico to start ninth grade. However, the traditional high school experience made it difficult to maintain her newfound sobriety.

“Honestly, I loved this school,” she says. “If I had not had substance abuse problems, it would’ve been an amazing fit for me. But at a big school like that, they can’t keep an eye on every kid at every moment.”

When she ended up back in residential treatment that summer, Kat’s parents struggled to establish a routine that would keep her safe when she returned.

“They emphasized that it was important to have the right support in place when she came home,” says Steven, Kat’s dad. “But the things they advocate for didn’t exist for people under eighteen in Virginia. The level of counseling and engagement you need to stay on track, it’s really tough to have those coexist with school.”

That’s when they began to hear about Chesterfield County’s plans for a high school program that supported students in recovery from substance use issues. It would open just in time for Kat’s sophomore year.

“It honestly came at the perfect time for us,” Kat says. “If it had opened a year later, I don’t know what I would have done for school last year or if I would be okay.”

What Is Chesterfield Recovery Academy?

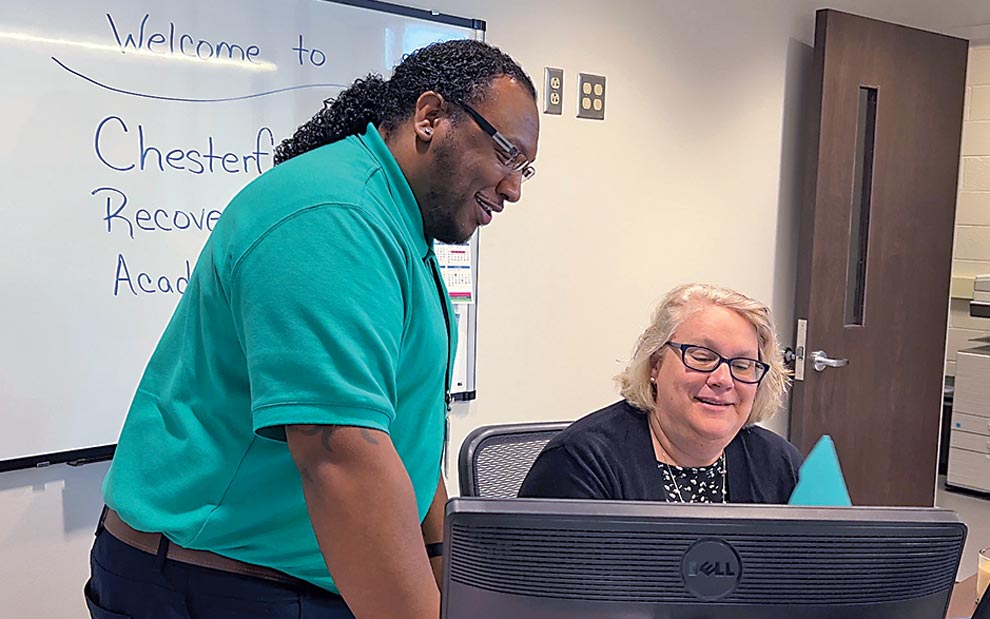

Designed to help students with substance use issues maintain their sobriety and make academic progress, Chesterfield Recovery Academy (CRA) is the first of its kind in Virginia.

“We have a full clinical staff,” says Justin Savoy, who was hired to coordinate the academy before it opened last fall. “The students have group therapy every day and individual therapy when they need it. It’s a year-round program, so the staff is available to students even when school is not in session.”

CRA serves students in grades nine through twelve with a variety of educational needs. Classes are held in person, but based on CCPSonline, Chesterfield’s virtual learning program. A staff of ten, including three clinicians, three peer-recovery specialists, two academic facilitators, and an instructional assistant, help students balance their academic goals with their recovery process. The lessons are tailored to assist each student in staying on track, making up lost ground where needed or even working ahead to graduate early.

There are forty-eight similar academies nationwide, and they address a growing problem: Substance-use disorders are on the rise, and teenagers are particularly at risk. The CDC reports that overdose deaths among Americans ages ten to nineteen years more than doubled between 2019 and 2021.

“Navigating high school is challenging enough for any student,” says school board member Dot Heffron, “but for young people who are recovering from substance use disorder, those challenges can be life-threatening.”

To help as many students as possible, CRA is open not only to Chesterfield County but to students from all fifteen divisions in Region 1, which stretches from Hanover to Sussex counties.

“Transportation is offered for all of them,” says Savoy. “And for families who prefer to drive themselves, we have vouchers to cover the cost of gas.”

Savoy emphasized that all students still belong to their home divisions while attending school in Chesterfield. Many find it helpful to maintain those connections while they attend CRA.

“They can still go to their own proms and graduate with their own class at home,” he says. “And they can choose to return to their home high school when they feel like it’s safe to do that.”

Because there is so much stigma around substance use disorder, Savoy also emphasized that the students’ transcripts will not include the words “recovery academy.” Instead, they will show each student was enrolled at CCPSonline.

Savoy says it’s been remarkable to see the changes in students during the year. “To see a teenager rebuilding trust with their parents, getting excited about their future, it just makes us all proud,” he says.

Heffron says that was evident at CRA’s first graduation ceremony in June.

“There was a wonderful energy of excitement, pride, and hope in the room,” she says. “CRA is a very special place, not just because it’s the only public recovery academy in the state, but because of the people who are there every day, dedicated to successful outcomes for the students.”

Savoy says their success has people talking about future recovery academies in other regions. Chesterfield Recovery Academy was featured in the Virginia School Board Association’s 2023 “Showcases for Success,” and he expects to see development of similar programs in Northern Virginia and the Tidewater area soon.

He also expects enrollment at CRA to grow closer to its current capacity of twenty-five students. During the first year, it started with only five students and grew to twelve. As of late summer, ten students were already enrolled for this next school year, and that number is likely to climb as students are referred to the program by their schools or families.

Kat’s Year at CRA – and What’s Next for Her

Kat says the first day at CRA was awkward, as the mix of ninth- through twelfth-graders got to know each other, but they soon formed close friendships.

“When you’re in group therapy with people, you know what their struggles are,” she says. “So it makes you much more patient, and you don’t take it personally if they’re kind of short with you or something.”

The one-on-one time with her therapist, Anna, is something Kat says was crucial to her success.

“She was amazing,” she says. “She really would listen and understand. Even outside of therapy, I was always excited to update her on my life. Whenever you need extra support, they are there.”

After her year at CRA, Kat says she feels strong enough to move on to a new setting. She’s starting her junior year at a private school where she says she can more fully prepare for her goal of attending art school after graduation. She says she can return to CRA if the need arises, but she feels ready for the next step.

Kat’s parents agree that it’s time, and they’re pleased with the progress she’s made.

“She’s very different now than she was a year ago,” says Steven. “She’s much more engaged with us and others; she’s calm and focused. Her whole outlook on life has improved.”

Carrie says this has been a tough road for her as a mother, but she has learned a lot and is happy to share her hard-won wisdom with other parents.

“Once you’re on this path [of addiction] there are only three outcomes,” she says. “One is prison, two is death, and three is recovery. And recovery is not a straight line. But the absolute most important thing is to just keep showing up and loving them.”

*Names have been changed to protect the privacy of the family sharing their story here.