You have just delivered your baby and are adjusting to the many surprises of parenthood when you receive a call from the pediatrician. After you exchange pleasantries, the doctor pauses and says, “Your baby has abnormal results from the newborn screening that was collected at the hospital and a repeat sample needs to be collected.”

In Virginia, newborns are tested for thirty-one disorders on the newborn screening panel, and your baby’s hemoglobin panel result raised a red flag.

After about a week, the second sample results are in and your baby has a type of sickle cell disease (SCD). The doctor recommends you schedule an appointment with a hematologist. Your mind is racing, and you are anxious … wondering what, how, why?

While rare, for approximately 100,000 Americans this scenario is extremely real.

Just as genes for eye color, hair color, and many other traits are inherited, so are genes for hemoglobin. Hemoglobin is the part of the red blood cells responsible for carrying oxygen throughout the body. The most common type of hemoglobin is hemoglobin A. Sometimes, however, there are changes to hemoglobin A and other types of hemoglobin are formed. Red blood cells that contain hemoglobin A are round and flexible; they move freely through blood vessels.

What is sickle cell disease?

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a group of blood disorders that affects red blood cells. SCD causes normal, round, flexible red blood cells to change into stiff, banana- or sickle-shaped cells. The change stops the red blood cells from freely moving and carrying oxygen throughout the body, causing episodes of pain or sickle cell crisis. It is a genetic condition, which means it is passed from your parents. Babies are born with sickle cell disease and cannot catch it from other people.

SCD is a lifelong condition and the only possible cure is a bone marrow transplant. A bone marrow transplant is only possible for a limited number of individuals who have a suitable donor. There are treatment options that can reduce the number of painful crises and prevent complications. People with SCD can live full lives by finding good quality medical care, having regular checkups, and learning healthy habits.

What is the difference between SCD and sickle cell trait (SCT)?

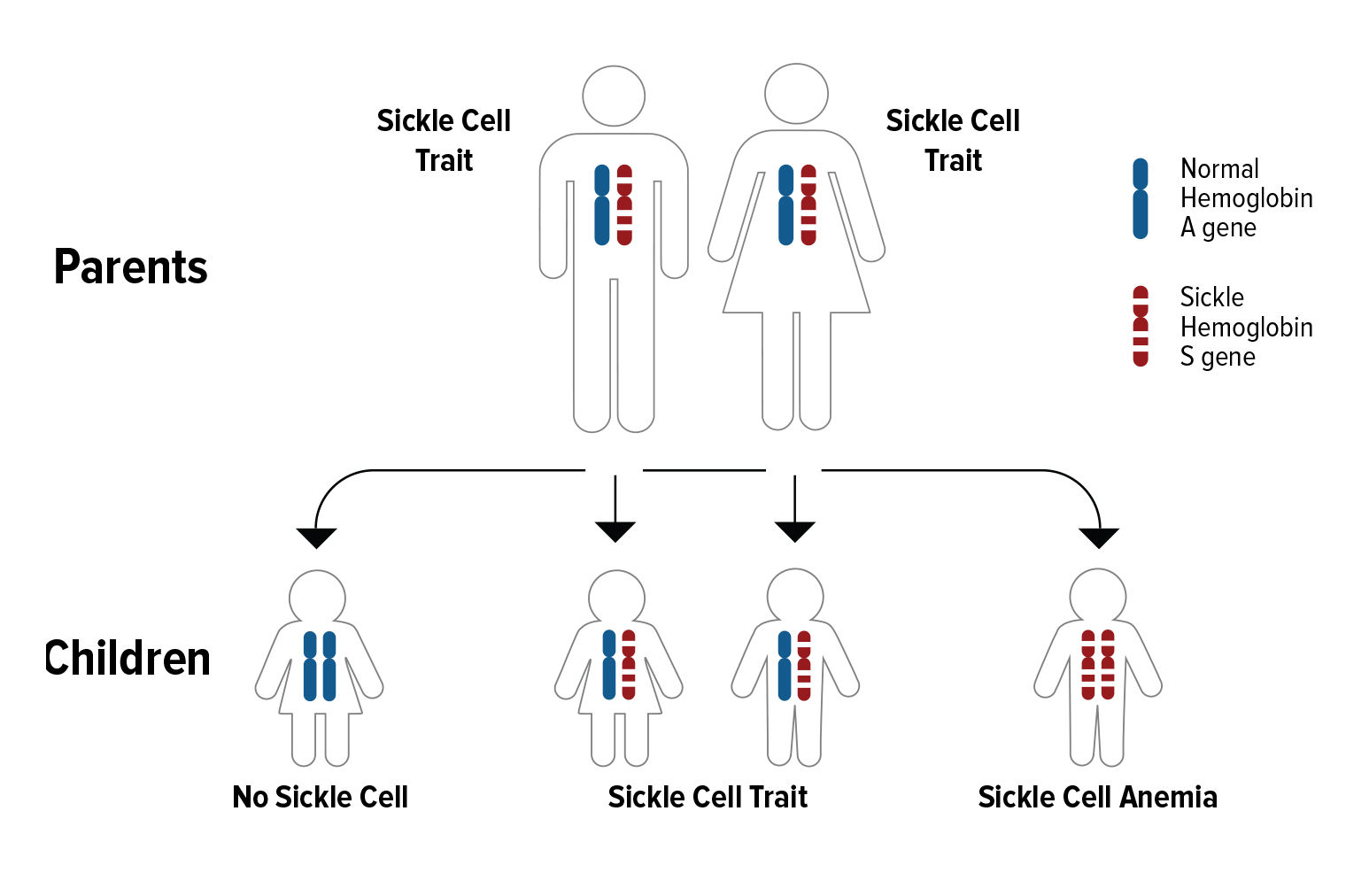

Sickle cell trait means a person has inherited one sickle hemoglobin S gene and one normal hemoglobin A gene. A person with SCT normally does not have any of the symptoms of sickle cell disease. A person with SCT can pass the sickle cell gene to their children.

If both parents have SCT, with each pregnancy:

- There is a 50% chance the child will have SCT

- There is a 25% chance the child will have sickle cell anemia, one of the most common types of SCD.

- There is a 25% that the child will not have SCD or SCT.

How do I know if I have SCD or SCT?

All infants born in the United States after 2006 are screened for their sickle cell status. People who may not know their trait status should get tested. It is a simple blood test, called a hemoglobin electrophoresis, that can be ordered by a healthcare provider. Ideally, you and your partner should ask for a blood test before you have a child.

For more information about SCD and/or SCT, visit: SicklecellVirginia.com.

For information on why sickle cell disease is more common in children of African heritage, go here.

Read about a recent innovation related to gene editing for treating sickle cell disease here.

[vcex_divider color=”#dddddd” width=”100%” height=”1px” margin_top=”20″ margin_bottom=”20″]

June 19 is World Sickle Cell Awareness Day, a day created to increase public knowledge and an understanding of sickle cell disease and the challenges experienced by patients and their families. Due to COVID-19, one of the challenges patients and families are experiencing is a lack of blood donations. Blood transfusions are a known treatment option for individuals living with SCD. Diverse donors are needed to help maintain the blood supply. Visit your local blood bank to donate blood.