Think back to the schools of yesteryear, the ones you and your siblings may have attended. Whether public or parochial there was most likely one teacher and one classroom for each grade. Children walked to their neighborhood school and knew what to expect when the school bell rang. Teachers wrote lessons on blackboards and taught the three essentials – reading, writing, and arithmetic. The atmosphere was comfortable and consistent.

Think back to the schools of yesteryear, the ones you and your siblings may have attended. Whether public or parochial there was most likely one teacher and one classroom for each grade. Children walked to their neighborhood school and knew what to expect when the school bell rang. Teachers wrote lessons on blackboards and taught the three essentials – reading, writing, and arithmetic. The atmosphere was comfortable and consistent.

Today, the world of education has changed and many parents are seeking alternatives to the traditional classroom. The shift began in 2000 with the landmark release of A Nation at Risk: The Imperative For Educational Reform, a report by the National Commission on Excellence in Education, which questioned whether schools in the U.S. were failing students. Since then, the majority of states have measured educational standards using the Common Core State Standards Initiative, and in Virginia, the Standards of Learning, to attempt to raise the bar in language arts and mathematics for grades K through 12. “The standards help us to set expectations,” says William C. Bosher Jr., EdD, executive director of the Commonwealth Educational Policy Institute. “They set the foundation for people to grow.”

While those standards are beneficial, some parents worry that their children are not getting a well-rounded education, and one that will prepare students to succeed in the world. Parents want a teaching environment that will boost their child’s creativity and curiosity and foster independence. Trying to meet the needs of every child can be challenging for public school systems. That’s why some parents turn to alternative plans for education that follow the principles of Waldorf, Reggio Emilia, or Montessori teaching methods.

Waldorf

Waldorf

Austrian philosopher Rudolf Steiner created this method of education in 1919 when he started a school at the Waldorf Astoria cigarette factory in Germany for the factory workers’ children. “He believed the only hope for peace was to educate children in a different way,” says Roberto Trostli, a teacher at Richmond Waldorf School.

Each Waldorf school is an independent school but all offer a spiritually based education. “Everything follows from the view that human beings are spiritual beings,” says Trostli. “The goal is to create the most human future by developing each child’s essential humanity.”

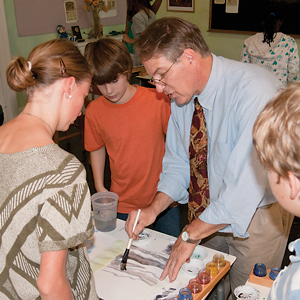

The Waldorf method is experiential, relative, and relational. It engages children’s imaginations and curiosity through hands-on learning. Teachers have autonomy in the classroom and often work with the same students through several grade levels, building lessons cumulatively. “The idea is to have a series of years with students so you can plant the seeds and nourish them,” Trostli says.

Instruction is built out of a relationship between teacher and student. “Not every child needs the same thing at the same time,” Trostli says. “The beauty of being attuned to students is that teaching is efficient.”

Nearly a century ago, in Germany, Steiner insisted that students learn world languages. “He felt like unless you learn the language you could never understand other people,” Trostli says, noting that Richmond Waldorf School teaches two languages – Spanish and Russian – to provide different cultural experiences for students.

Children also learn instrumental music, either flute and recorder, or violin or cello. Every child does handwork and woodwork and participates in movement classes. “It’s a very well-rounded and rounding education,” Trostli says, adding that every lesson at the school is infused with art. “All the different arts are part of your vocabulary and repertoire to help teaching and learning be as alive as possible. Learning and the joy of learning are infectious and part of the process.”

Reggio Emilia

Reggio Emilia, named after a Northern Italian town, is a progressive education approach created by a young teacher, Loris Malaguzzi, after World War II. The researchbased approach is grounded in the idea that the work of the children emerges from their interest and is done with cooperation and collaboration with their classmates.

“It’s more toward interdependence,” says Marty Gravett, director of early childhood Education and outreach at Sabot at Stony Point. “Always at the heart is the recognition that each individual has responsibility for the learning of the community.”

Classroom projects are often referred to as investigative research. Children are encouraged to use various modes of expression in their learning. “We try to find ways that children can collaborate and share their learning,” Gravett says. “All of it is about learning to trust yourself as a learner and researcher. It’s taking risks, thinking analytically, and problem-solving.”

The Weinstein JCC Preschool became interested in Reggio Emilia about 15 years ago. “It is a child-centered approach versus a teacher-directed approach,” says donna Peters, the school’s early childhood director. “Teachers get to know the children so they can understand who they are and their learning styles through play, actions, and conversations. They are looking for a seed of something that could be of interest and build into a project.”

The Weinstein JCC Preschool became interested in Reggio Emilia about 15 years ago. “It is a child-centered approach versus a teacher-directed approach,” says donna Peters, the school’s early childhood director. “Teachers get to know the children so they can understand who they are and their learning styles through play, actions, and conversations. They are looking for a seed of something that could be of interest and build into a project.”

The outside environment plays a large part in a child’s learning. “We bring nature into the classroom. We try to create a beautiful environment to inspire children,” Peters says. “We create a physical environment that is calming and beautiful.”

The school fosters an atmosphere where children can explore and pose questions. “Teachers are like researchers,” Peters says. “They help the children become detectives.”

Teachers and children alike are excited about the program. “The children learn to work together and come together with their ideas. It builds confidence,” Peters says. “For the teachers, it’s not boring because you are not teaching the same tired lesson plans.”

Montessori

Montessori is a philosophy of education developed by Italian physician and educator Maria Montessori over a hundred years ago. “She started working with children in an orphanage who were not supposed to be able to learn,” says Amanda Edmondson, director of Tuckahoe Montessori School. “She looked at them developmentally and how they were taking in information.”

The Montessori method supports a child’s natural development, helping children learn with their senses. As they progress through the program, they develop creativity as well as problemsolving skills, critical thinking, and time management prowess that prepares them to be able to contribute to society.

Schools using this form of education focus on inter-discipline and independence. Children are free to move around the classroom and are able to learn about subjects that interest them. “Children look at education differently when they are able to take ownership,” Edmondson says. “They want to do the work and have success.”

Teachers help foster a child’s inner curiosity. “Kids are excited to come to school,” Edmondson says. “That is what you want. You want children to be excited. They know they are in charge of what they are learning today. They are fully engaged.”

Students and parents alike find the school’s mixed-age classrooms beneficial. “In our classrooms we have 3- to 6-year olds together as opposed to a traditional preschool classroom,” Edmondson says.

As part of their daily tasks, children learn to multi-task. “They don’t have to sit and wait for direction,” Edmondson says. “It’s a dynamic environment. Children are passionate about learning when they leave us.”

When it comes to parents making a choice about their child’s education, dr. Bosher believes they need to do their homework and learn about the various types of education. Parents can scan the Internet for information or talk with other families who have chosen a different educational path for their children. “A lot of parents spend more time choosing a car than they do a school,” he says. “It’s critical that families make discerning decisions about schools that are the best fit for their children.”