Have you noticed nandina growing in your yard or your neighborhood? How about English ivy or Japanese honeysuckle? While beautiful to some and commonly used in residential landscaping, invasive plants like these are actually a silent danger to our local ecosystems. They can easily get out of control and escape beyond our yards into parks, forests, and conservation areas. Over time, they alter natural processes and compete with other vegetation, which can lead to the extinction of native plants and animals. But here’s the good news: You have the power to stop them from spreading.

You may be wondering two things: what makes a plant invasive; and why should I care? An invasive plant meets the following criteria: 1) it was brought by humans (intentionally or accidentally) to a geographic region other than where it is naturally found; and 2) it is harmful to the environment, human health, or the economy in the area where it has been introduced. Invasive plants usually have the following characteristics: they grow and spread quickly; they disperse a lot of seeds; they out-compete native species for critical resources including light, water, and nutrients; and they require significant amounts of time, energy, and/or money to control.

You might also be questioning why these plants are still sold in garden centers and nurseries. Our lawmakers may be wondering the same thing. Earlier this year, the Virginia General Assembly passed HJ527, a bill to study the sale of invasive plants (or the many others) in order to inform policy changes that will “eliminate the sale and use of invasive plant species in the Commonwealth and promote the sale and use of native plants.”

As important as this initiative is, it only addresses future plantings, not the invasives that are already taking over our forests.

Here’s how you can help reduce non-native plants in the environment:

The first step of any change is awareness, so here are six invasive plants you’re likely to see in your neighborhood. By choosing not to plant these invasive species (or the many others identified by the Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation) and by taking action to safely remove them when you see them, you can play an active role in conserving Virginia’s native landscape.

Don’t worry, we have suggestions for replacing these plants, too, with specimens that are beautiful and also provide food and habitat for our native creatures.

Together, we can create an environment that fosters diverse communities of plants, insects, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and mammals, all while showcasing the beauty of Virginia natives.

1. Nandina domestica, [Nandina domestica] commonly called heavenly bamboo and sacred bamboo, is an evergreen shrub in the barberry (Berberidaceae) family. Nandina blooms in late spring and develops clusters of red, two-seeded berries in late fall and winter. Across the Southeast, nandina has escaped cultivation and invaded forests. Aside from forming dense thickets that displace native plant communities, its berries are poisonous to people, pets, and wildlife. If there aren’t other foraging options, birds (who also inadvertently spread seeds) will gorge on nandina berries. This has been known to kill birds of several species, most notably cedar waxwings.

Native (and bird-friendly) alternatives: winterberry holly or (Ilex verticillata), yaupon holly (Ilex vomitoria), which you can also use to make a caffeinated tea.

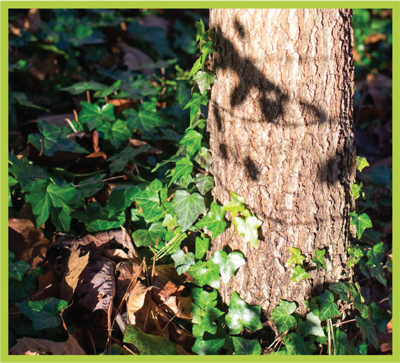

2. English ivy (Hedera helix) is an evergreen, perennial woody vine in the ginseng (Araliaceae) family. It has tiny greenish-white flowers that bloom in late summer or early fall, and after the flowers fade, it has bluish-black berries. The problem with English ivy is that it vines up and suffocates trees. In fact, mature vines can grow up to one hundred feet high. Not only does this block foliage from receiving sunlight, but it also damages tree bark by holding moisture against the trunk. The weight of the vines also makes trees more vulnerable to collapsing during extreme weather events. If you have English ivy on a tree, it’s a good idea to cut the ivy near the ground and return later to remove the dried vines to avoid damaging the bark. Of course, you will also want to remove the roots from the soil. Fortunately, roots are easy to pull out by hand, especially after a rain.

Native alternatives: wild ginger (Asarum canadense), crossvine (Bignonia capreolata), partridge berry (Mitchella repens), Virginia creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia) and golden ragwort (Packera aurea).

3. Chinese privet (Ligustrum sinense) is a member of the olive family (Oleaceae). It blooms in late spring and has small white flowers. The fruits, though toxic to humans, are spread by birds, which can accelerate its takeover of native plant communities. Chinese privet has naturalized in environments ranging from forest understories and streamsides to disturbed environments like roadsides. In forests, it dominates the shrub layer, shades out all herbaceous plants, and suppresses the growth of tree seedlings.

Native alternatives: blackhaw (Viburnum prunifolium), devil wood (Osmanthus americanus) and Carolina cherry laurel (Prunus caroliniana).

4. Japanese honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica) is a member of the honeysuckle (Caprifoliaceae) family. Evergreen to semi-evergreen, the leaves of Japanese honeysuckle are usually present year-round in Virginia. Fragrant blooms, which change from pale pink to cream-yellow as they mature, begin in late spring and last through summer. Japanese honeysuckle competes with native vegetation both above ground (by twining around trees and shrubs) and below ground (by sending out runners, or stolons). Like English ivy, Japanese honeysuckle vines can damage tree bark and make trees more susceptible to falling during storms.

Native alternatives: coral honeysuckle (Lonicera sempervirens), Carolina or yellow jessamine (Gelsemium sempervirens), maypop (Passiflora incarnata) and Virginia creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia).

5. Porcelain berry Ampelopsis glandulosa var. brevipedunculata (or Ampelopsis brevipedunculata), is a member of the grape family (Vitaceae). This deciduous, woody vine develops extensive root networks, making it difficult to eradicate once established. Its tiny white flowers bloom in mid-summer, followed by the colorful transformation of its berries from white to yellow, lilac, green, and turquoise. Birds and small mammals spread this plant over long distances by eating its fruits, but it can also grow rapidly from root fragments. Like others on this list, porcelain berry shades out native trees and shrubs as well as understory vegetation.

Native alternatives: crossvine (Bignonia capreolata), Carolina or yellow jessamine (Gelsemium sempervirens) and coral honeysuckle (Lonicera sempervirens).

6. Italian arum (Arum italicum) is an herbaceous perennial in the arum (Araceae) family. It has arrowhead-shaped leaves that appear in late fall and winter and die back in the summer. This invasive species spreads prolifically both by seed and underground through tubers. It has orange-red berries that grow in oblong clusters, and the berries can be toxic to humans and wildlife. Its oils are a known skin irritant. Italian arum forms a dense groundcover that shades out other plants. The areas next to streams and rivers are sparticularly susceptible to invasion. Italian arum also has the ability to survive harsh winters, giving it another advantage against some native vegetation.

Native alternatives: jack-in-the-pulpit (Arisaema triphyllum), wild ginger (Asarum canadense), Allegheny spurge (Pachysandra procumbens) and mayapple (Podophyllum peltatum)

In Richmond, you can find the native plants recommended here at a range of local nurseries. Let’s all do our best to spread the word on invasive plants – though not their seeds! – with our family and friends. This way, we and future generations can continue to enjoy our beautiful natural environment.