My four-year-old’s favorite part of the Ladybug Girl by Jacky Davis and David Soman is when the main character is standing in the middle of her messy room and she says she’s bored. Lily always laughs and says, “That’s crazy! She’s got all those toys. How can she be bored?” Still, as parents, we are all too familiar with this scenario.

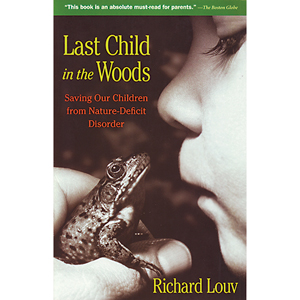

“Especially during the summer, parents hear the moaning complaint: ‘I’m bored.’ Boredom is fear’s dull cousin,” writes Richard Louv. “Passive, full of excuses, it can keep children from nature – or drive them to it.” After reminiscing about how bored wasn’t in his grandmother’s vocabulary, he explains what we already know. “Today, kids pack the malls, pour into the video archived, and line up for the scariest, goriest summer movies they can find. Yet, they still complain, ‘I’m bored.’ Like a sugared drink on a hot day, such entertainment leaves kids thirsting for more – for faster, bigger, more violent stimuli.”

Louv argues that parents and caregivers need to address the difference between a “constructively bored mind and a negatively numbed mind.” He says eventually “constructively bored kids turn to a book, or build a fort, or pull out the paints and create, or come home sweaty from a game of neighborhood basketball.” So what turns a numbed mind into a constructive one? Parents need to “detach their kids from electronics long enough for their imaginations to kick in.” If your child participated in National TV Turn Off Week, you may have even seen this in action. Thanks to turning off our TV, my girls started on the construction of their third fort in our woods this week.

Once you’ve got their attention, then you need to find a balance between independence and supervision, making sure that you don’t stifle the fun out of their unstructured time. “If a child is to keep alive his inborn sense of wonder,” wrote Rachel Carson, he or she “needs the companionship of at least one adult who can share it, rediscovering with him the joy, excitement, and mystery of the world we live in.” This can be hard to do because, as Last Child in the Woods points out, “parents must walk a fine line between presenting and pushing their kids to the outdoors.”

Louv suggests you start by encouraging your child to get to know a ten-square-yard area at the edge of a field, pond, or pesticide-free garden. He repeats the old Indian saying: It’s better to know one mountain than to climb many.” Sit. Observe. Wander. Maybe, you can even keep a journal of the changes over time with drawings, pressed flowers, or details about the weather.

Why not try a “moth walk”? “In a blender, mix up a goopy brew of squishy fruit, stale beer or wine (or fruit juice that’s been hanging around too long) and sweetener (honey, sugar). Then, take a paintbrush and…go outside at sunset. Slap some of this goo on at least a half-dozen surfaces…Come back when it’s dark and look at what you lured.”

And when all else fails, read about nature. While reading is an indirect experience, like television, it “does not swallow the senses…Reading stimulates the ecology of the imagination.” Louv recalls the wonder her felt from books like Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn, even The Lord of the Rings. Any author whose passion for the natural world comes across on the page is one worth reading.

I think the key is doing something you enjoy for enthusiasm is contagious. We don’t garden, but we do compost. Over a year ago, the white oak out back had cast dozens of acorns into our yard. When tiny trees popped up last spring, my girls convinced their father not to mow over them. Instead, they’ve used the soil from our compost to pot the tree saplings so they could be distributed this Earth Day. Naturally, reuniting your kids with nature isn’t as simple as passing out trees once a year, but it is part of a greater effort to bring nature home. With the help of schools, nature organizations, city planners, and of course, other parents, you can close the divide between your children and nature. It’s just a matter of making every day Earth Day.